© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Literary history has never been a chronicled, steady stream of periods, works and authors but rather it is defined by literary contemporaries through their dynamic debates on the subject. Whether an author will go down in history often comes down to the opinion of the critic or historian assessing the work. The success and lasting power of an author or a particular literary work depend on a mixture of elements including the reaction of the audience – at the time it was written and in the future – the attitudes of editors and the how it is received by critics and literary historians over the course of time. As time progresses and societies evolve, attitudes toward certain works can shift due to these factors, leading to once-prominent authors losing their status.

Abdülhak Hamid Tarhan was considered a great author until critical writings against him by young authors of the early Republican era, including Nazım Hikmet and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, tarnished his reputation. Despite being a master of his time, he was left behind following the heavy critiques of the newer generation and became a matter of controversy for literary historians trying to discern the significance he held in the Tanzimat age.

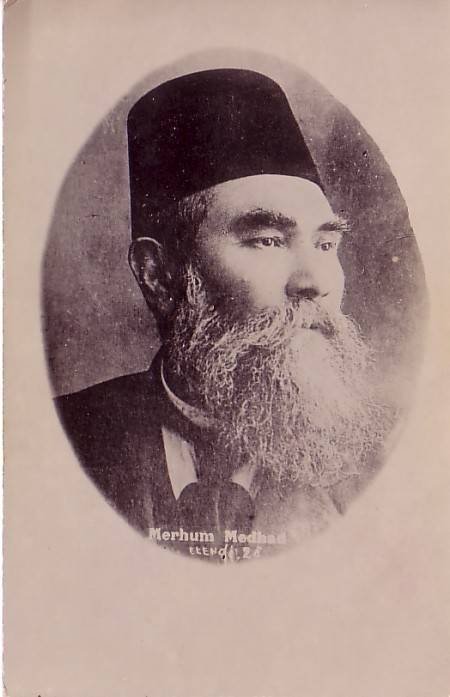

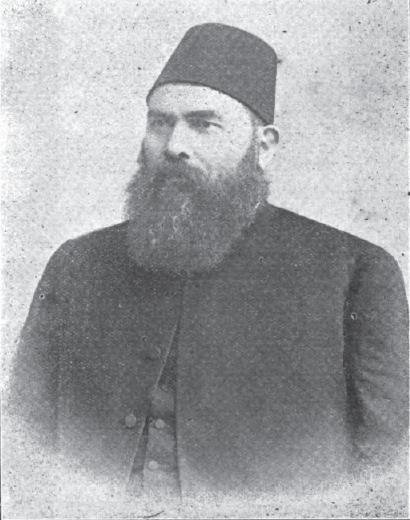

On the other hand, literary historians also have the ability to do the inverse and resuscitate forgotten works and authors. Ahmet Mithat Efendi for example was a celebrated author in his time but was completely forgotten during the Second Constitutional and Republican years until he regained significance in the late 1980s and 1990s, when postmodernism was celebrated in Turkish literary circles. Mithat had nothing to do with postmodernism but his criticism of the over-Westernization of elites and his writing style, in which the author would interject in the prose, was happily received by postmodernist critics. Mithat's works, as a literary fiction dilettante, placed him in a peculiar position during the reformation of Turkish fiction which had previously been based on solid realism.

Early life

Mithat is the archetype of the Turkish fiction writer brought up in poverty, born in 1844 in Istanbul to a lower-middle-class family of shopkeepers. His family was of Caucasian descent, who fled the Caucasus due to the 1829 Ottoman-Russian War. His father ran a shop in Istanbul’s famous Spice Bazaar, which is still active to this day, selling cloth. After his father’s sudden death, Mithat was sent to his brother’s home in Vidin on the southern bank of the Danube, in Bulgaria today, where he began his education before returning to Istanbul to finish elementary school in the Tophane quarter.

Following the loss of his father, Mithat worked as an apprentice at a herbalist in the Spice Bazaar, where the shopowner would often beat him. Fortunately, his elder brother was working with Mithat Pasha at the time, who was the leader of constitutional reformation and took a liking to Ahmet Mithat, too, and made him a lower-ranking clerk when he became governor of Nis, in today's Serbia, in 1861, changing Mithat's life trajectory.

Mithat Pasha made Ahmet Mithat finish secondary school and learn French before he began working as a public servant at the governor’s office in 1864. He married in Sofia, where he worked translating for engineers, in 1866. Mithat was always fond of writing and began to write columns for the local newspaper "Tuna," published for the Balkan regions of the Ottoman state, before taking over as editor-in-chief in 1869.

Self-made author

Ahmet Mithat followed his elder brother and Mithat Pasha to Baghdad, where he edited the “Zevra” newspaper and wrote two of his early works, “Hace-i Evvel” (“The First Teacher”), a popular book of philosophy and science, and “Kıssadan Hisse” (“Moral of the Story”), a tale with very clear moral messages. These two early works show Mithat's attitude toward writing. He was not interested in writing elaborate, elevated prose but wanted to ensure his message clearly reached a vast audience, which he kept on his side by remaining impartial in his writing and remaining centered when exploring issues. Another thing made clear was that Mithat's ambition was to achieve fame and wealth as soon as possible.

After his elder brother’s death, Mithat returned to Istanbul for the last time. He was now editor-in-chief of the military journal “Ceride-i Askeriyye” but had bought a printing machine and had begun to publish his own books, a profession he would continue for the rest of his life.

His printing business was so successful that he had to open a separate printing house first in the Sirkeci quarter, the center of business in Istanbul, and then in the Beyoğlu district, frequented by intellectual circles. Besides his own books, Mithat published various periodicals both to make money and to enlighten literary crowds.

Accidental adversary, deliberate conformist

Although Mithat was a moderate, apolitical author, he was exiled together with the Young Ottoman faction to Rhodes because of an article in which he defended materialism, a concept he would later come to reject. While exiled he met Namık Kemal and wrote in the great author’s newspaper “Ibret.” After three years of exile, Mithat was pardoned by the new sultan after the previous one was overthrown by the Young Ottomans.

Although he was on good terms with the Young Ottomans, especially their supreme leader Mithat Pasha, Ahmet Mithat did not wish to continue his life as a politician. He instead became a publisher and author. In 1878, he began to publish “Tercüman-ı Hakikat,” one of the longest standing newspapers of the Ottoman era. During the Sultan Abdülhamid II era, Mithat became a conformist and did not publish anything that would displease the sultan or government, who in turn supported all apolitical works by intellectuals – garnering him the personal support of Abdülhamid II.

Thanks to the royal endorsement, Mithat was appointed to various governmental posts including running both the state newspaper, “Takvim-i Vekayi,” and the royal printing house, “Matbaa-i Amire,” as well as overseeing the public health institute. Mithat represented the Ottoman State at the Orientalism Conference held in Stockholm in 1889 and often taught students at Darülfünun (today’s Istanbul University).

Novelist

Mithat is considered an important figure to this day for his writing of long fiction. He wrote 32 novels, many of which were published in periodicals section by section because they touched on popular causes at the time. Mithat's writing style was simple yet open-hearted, and while his imagination tended to veer toward the oriental, he never allowed the facts to be overshadowed by his fiction. He expertly manipulated the reader's curiosity through his adventurous tales, often stretching the stories out to try and reach a larger audience and extract more money.

Many of his works have not aged well and no longer reflect the sentiments of today's reader, but reading Ahmet Mithat to this day is entertaining, even if you would not categorize him as one of the great storytellers. His novels can be used as a tool for social scientists when trying to paint a picture of daily life in Istanbul at the time because of the great detail he has poured into his works.

Mithat retired after the Sultan Abdülhamid II era was ended by the 1908 revolution. He died in 1912 in Istanbul.