© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Turkish American composer, pianist, singer and multi-instrumentalist Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol is a maestro whose art effortlessly fuses the melodies of Turkish music with the innovative frontiers of contemporary jazz.

I met him for an interview at a showroom, engrossed in inspecting an exclusive design by Arzu Kaprol, which he had commissioned to wear at the Grammy Awards ceremony, where his album is a nominee this year. Then, we moved to the place where we were supposed to conduct our interview. However, delving into the depths of Sanlıkol's artistry and intellect? Oh no, a mere interview won't cut it. It would take at least a weeklong meeting to scratch the surface of his complexity.

Getting his second Grammy nomination, Sanlıkol was nominated in the Best Engineered Album, Classical category for his album "A Gentleman of Istanbul" – a collaboration with A Far Cry string orchestra founded by numerous alumni from the New England Conservatory.

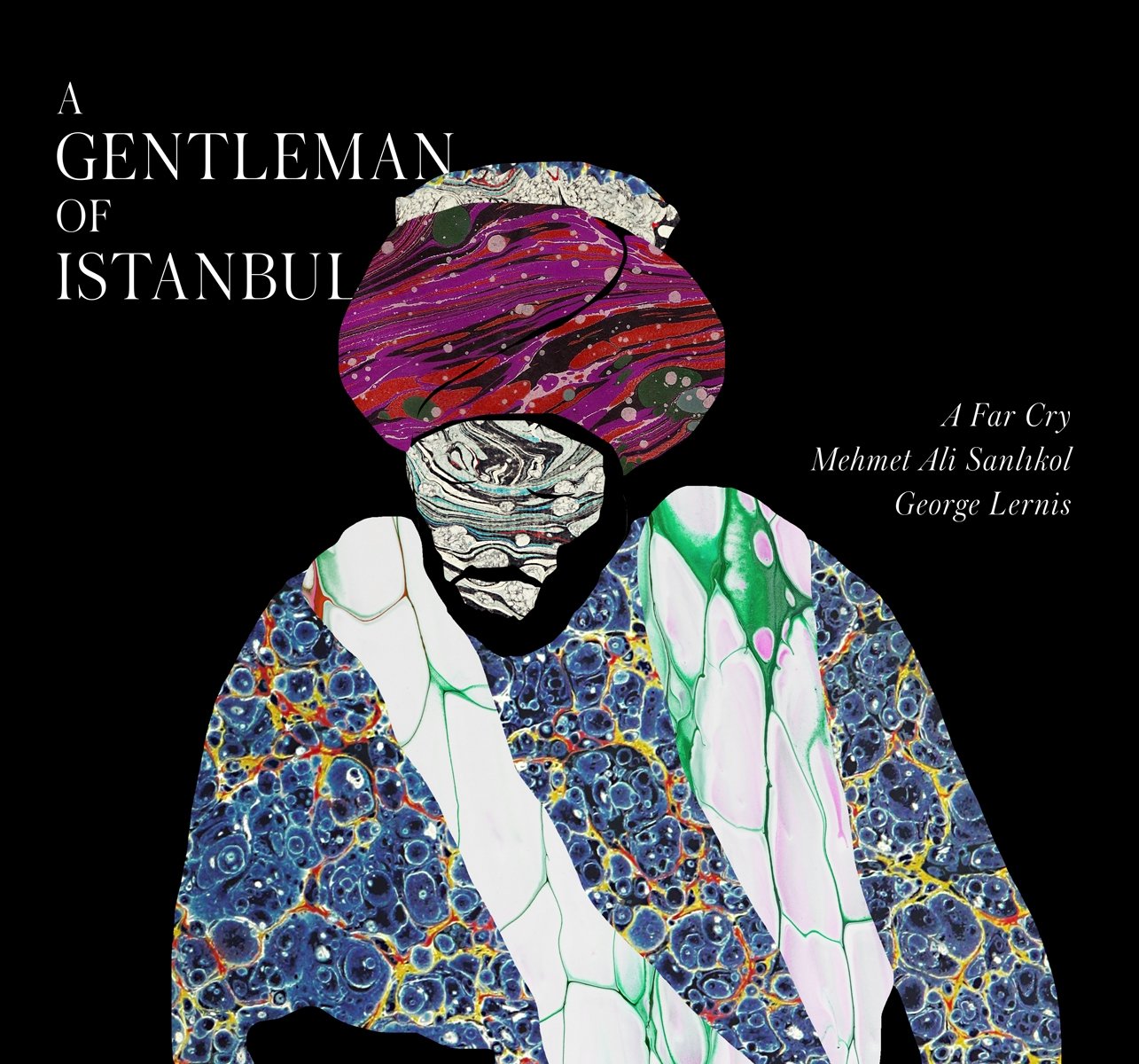

Frankly, from the album cover to the music videos, all aspects of the creative process of "A Gentleman of Istanbul" have been meticulously curated; for this reason, we can genuinely call it a work of art.

Therefore, when you see the album cover, you first notice a character depicted through the art of marbling, ebru. Sanlıkol chose the word gentleman to describe the honorific historical title of çelebi in Turkish as a respectful nod to the renowned 17th-century Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi.

In Turkish culture, an Istanbul gentleman would perhaps be defined as a "polite, considerate, well-mannered, tolerant, well-educated, humble, honorable, kind-hearted, mature and noble person; in essence, a good-natured, capable individual." Obviously, it's quite challenging for all these qualities to converge within one person, and historically, a gentleman of Istanbul wasn't necessarily a common type encountered at every turn.

In fact, Sanlıkol's starting point here actually stems, to a certain extent, from former U.S. President Donald Trump's rhetoric of promising to ban Muslims from the country. But rather than as a direct response to Trump, he realized inadvertently in the protests against Trump, wherein the media, press, major newspapers like The New York Times, or on placards held by the protesters, that there were generally very cliched images of Muslims – such visuals indeed exist. It was either women in veils or a bunch of men praying inside a mosque.

In fact, he realized that unwittingly, the protests were inadvertently reinforcing the stereotype Trump was putting forward.

"It was a depiction as if there's been no progress, just as Edward Said described it. It is almost as if Islamic culture has been stagnant for 300 or more years. As if we haven't progressed and remained frozen in time," he explained.

"I wanted to call out to Americans, 'Look, let me show you a real deal Muslim intellectual, for example, someone like Evliya Çelebi, to blow your hats off.'"

"The concept of a 'gentleman' that I originally had in my mind found its translation in Evliya Çelebi. In the 17th century, not only were the intellectuals of Istanbul the 'çelebis,' but also the way the term gentleman was used back then in Europe more or less corresponded to a çelebi in the Ottoman world indeed. Since Evliya had a cosmopolitan stance and held a very pluralistic view, I figured that he indeed was "A Gentleman of Istanbul'" he said.

Sanlıkol goes on to discuss Evliya Çelebi's stories at this point. He talks about Evliya being a storyteller while mentioning how he entered the most important church in Vienna, St. Stephen's Cathedral, during the Vienna campaign and listened to an organ performance. Apparently, Evliya described this as one of the most enchanting music he heard in his life. On every page of Çelebi's greatest work, "Seyahatname" ("Travelogue"), he points out how he sometimes entertains with stories, acting as a storyteller and at other times takes on the identity of a historian. According to Sanlıkol, one of the most significant aspects of the passages he selected is Çelebi's reference to Alexander the Great as Dhu al-Qarnayn in the Quran.

Therefore, the album, like Çelebi's rich, culturally sophisticated world, is wildly designed as an interdisciplinary album. Sanlıkol had meticulously compiled all the scenes he saw when he closed his eyes, bringing them to life with music and narratives. Hence, this album isn't a collection of songs that can be listened to and passed over in a single sitting.

Moreover, he presents Turkish music and the ancient culture of the Ottoman Empire in his works, but he definitely doesn't approach it with an Orientalist perspective. On the contrary, he begins the creative process with a highly refined approach. While perfectly reflecting Turkish culture, he skillfully and sophistically dismantles the taboos associated with that culture. The people also come alive in the most original way for Sanlıkol because he imagines things as if they're a film.

"However, it's important to note that exoticizing and fantasizing are part of human nature. Yes, how one says 'wow' when they first see something foreign is how they, even if unintentionally, start also turning that something into an exotic image. Simply because it's foreign, this is within all of us. However, if, for just a minute, one could say, 'what is happening here?' then it is possible to attain awareness and dive deeper," he explained.

If we return to Evliya Çelebi, "A Gentleman of Istanbul" consists of four parts. Each of these four parts is adorned with constant allegories from Çelebi's "Seyahatname" ("Travelogue"), as in the fourth section, which is named Alexander the Great, he recites the Quran. "Right in the middle, the music stops and suddenly, nothing happens. And you hear the verse about Dhu al-Qarnayn, referred to as in the Quran. I recited that verse," he explained.

The second part, "The Death of Kaya Sultan," is a jazz ballad addressing the death of Melek Ahmet Pasha's wife during childbirth and takes on the tone of a Homeric elegy, also hinting at a form of entertainment with dramatization. "For instance, he writes them so beautifully by employing exaggeration, but within that exaggeration, there is art; for example, he says, 'Eyüpsultan was filled with hundreds of thousands of boats,'" Sanlıkol explained.

"The Vegetarian Dervishes," which notably caught my attention, is about an encounter in North Sudan, Africa, where two men approach from afar toward Evliya. "Both of them appear as dervishes riding fantastic animals. As they come closer, food is offered, but the dervishes decline, stating they do not eat meat. So, technically, they are 'vegetarian dervishes.' When asked why they do not consume meat, they recount a story of being held captive in Portugal, having to eat a friend who died while rowing on a ship due to years of starvation. Later, a storm strikes, and they land on a nearby island, where they make a vow never to eat meat again. After making this vow, two animals come and prostrate before these dervishes," he recalls the story. In this particular case, it is from such a world of fiction that Sanlıkol drew inspiration.

Bilingualism and dual identity make Sanlıkol a perfect interpreter between two cultures. Seven years after moving to the U.S., his interest in Turkish literature and music, particularly, reached a certain level of consciousness. Hence, in Sanlıkol's song titles such as "New Orleans Çiftetellisi," "Karagöz on the Orient Express" and "Vegetarian Dervishes," we hear names that sound utopian. However, when you listen to the songs and grasp their stories, you easily see how these concepts can come together.

"When I got accepted for my D.M.A. (doctor of musical arts), feeling confident, even a bit arrogant, I was 25 and feeling successful. I had achieved some success in Türkiye and especially in the U.S. Therefore, not being able to completely decipher the musical nuances of a simple and short folk song (entitled "Genç Osman") with a full Western education at this time resulted in an identity-related issue to arise and overcoming this identity issue took a long time," he explained.

"I see myself as a good interpreter. Because I have been living in the U.S. for many years, I have become fixated on Turkish literature. Sometimes, I even criticize our musician community a bit on a related issue. We musicians tend to get too absorbed in music and other areas; we, especially performers, tend to remain somewhat shallow. In fact, musicians tend to have a particular habit: due to their limited studies of other disciplines (such as history, philosophy, etc.), even though they deeply feel the many abstract and spiritual aspects of music, they cannot quite find the words to describe such phenomenon as a result of which expressing themselves often becomes superficial," he elaborated. And continued humorously critiquing such conversations among musicians: "Brother, you know. Yeah, man. I know. You know what I'm talking about. Yeah, you got me."

In this context, while making a sophisticated cultural synthesis, dual identity is both a blessing and a curse, according to Sanlıkol. However, what caught my attention the most was how "New Orleans Çiftetellisi" came about. Çiftetelli's rhythm is characterized by a 2/4 or 4/4 time signature with a distinct emphasis on certain beats in such Turkish music.

"Even though that piece is essentially a fun one, its core is quite sophisticated. When someone dies in New Orleans, they go out and walk and make a parade. That second line in the parade comes from one of the classic sentiments of jazz. I was thinking about the Turkish second line and heard my synthesis of a 'New Orleans Çiftetellisi' there." (Sanlıkol plays the rhythms and connects them to çiftetelli rhythms.) When you hear the name for the first time, this combination that seems impossible suddenly shows how harmonious and similar they are to each other.

His seventh album, "Turkish Hipster," also thematically captivates and winks at an ideology similarly.

"Many of us aren't very familiar with hipsters. Some confuse 'hipsters' with 'hippies,' but in reality, there's a historical difference between them. Hipsters are generally known as a group of emerging jazz musicians in the early 1940s. This movement stemmed from individuals who pioneered modern jazz. Figures like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were part of the hipster movement when they first emerged," he explained.

"During those years, this group opposed the commercialization of jazz and were busy forming their own styles. Hipsters usually had a distinct fashion sense and attitude, often adopting an unconventional style according to the period in which they lived. They played music at very fast tempos to prevent anyone from dancing," he elaborated.

With his choice of glasses on the album cover and wearing a turtleneck sweater, Sanlıkol subtly nods to the "fancy" ideology of these very hipsters. According to Sanlıkol, his "Turkish Hipster" album defines his music and intellectual spectrum, with "tales" ranging from swing to psychedelic (and with a nod to the legendary Turkish Rock musician Erkin Koray) from the perspective of being a hipster.

"I can tell you musical stories ranging from swing to psychedelic, and I think that's pretty hip," says Sanlıkol, smiling.

The concert scheduled at the Cemal Reşit Rey Concert Hall (CRR) on Feb. 24 will notably include the debut performance of "A Gentleman of Istanbul" in Istanbul. Sanlıkol mentions that the artistic director and chief conductor of CRR, Murat Cem Orhan, and his team are engaged in extensive preparations for this occasion.

Additionally, during the same week, the artist will be performing in Bursa, where he grew up, as part of a new exhibition that will open at the Musical Instruments Museum, where he acts as the curator and the project director.