© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

A laser-powered study of the sprawling metropolis of Calakmul in southern Mexico offers tantalizing new evidence that it may have been the most crowded ancient Maya urban center during the civilization's classical peak some 1,300 years ago.

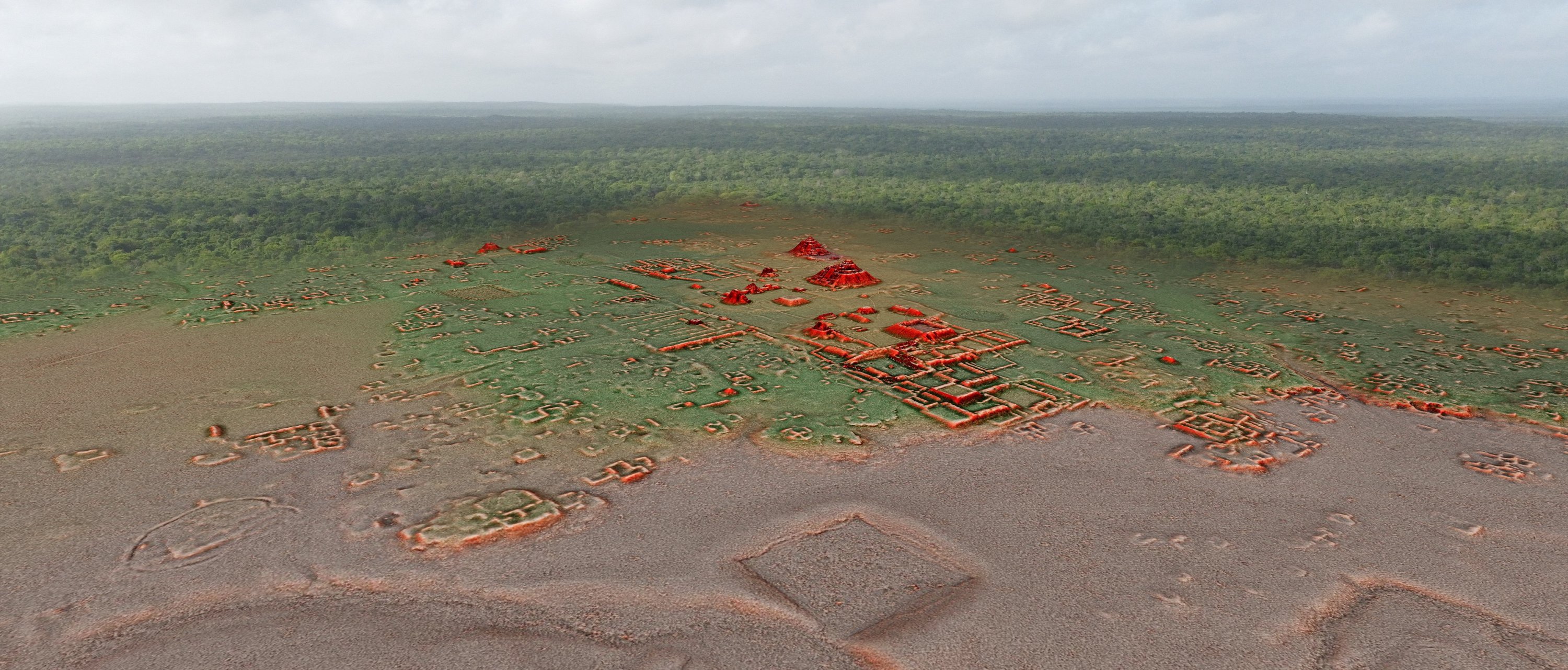

The new LIDAR study announced late Wednesday by Mexican antiquities institute INAH covers the jungle-covered ruins of once-mighty Calakmul, located in the central lowlands of the Yucatan peninsula near the Guatemalan border. Calakmul thrived during the Maya's classic-era zenith from around 250-900 A.D., boasting massive pyramids, palaces and temple complexes, only a tiny portion of which have been excavated.

At its peak, it was ruled by fearsome Snake dynasty rulers who jostled for power with other kingdoms at a time of major human achievements in writing, math and art throughout the Maya world in present-day Central America and southern Mexico.

Kathryn Reese-Taylor, a University of Calgary scholar affiliated with the LIDAR study, explained in a webcast that new maps of the site reveal numerous previously unknown buildings showing that Calakmul was denser than even Tikal, the ancient Maya metropolis located in northern Guatemala long thought to be the civilization's biggest urban center.

LIDAR mapping technology uses planes to shoot pulses of light into dense forest canopies, allowing researchers to peal away vegetation and reveal ancient structures below.

Reese-Taylor noted the new preliminary maps of the barely three-month-old data show extensive residential apartment complexes clustered around temples and possible markets.

She added that by around 700 A.D., Calakmul's physical footprint equaled that of modern-day Amsterdam or Brussels. Previous estimates suggested the city's population likely reached some 50,000 inhabitants, but the new study could force a recalculation.

INAH said in a statement that the sheer density of the buildings points to a big population and suggests that all available land was modified by the Maya, including previously unknown water canals, terraces and dams likely designed to protect water supplies and boost farmland.

"There are so many details, big and small structures," said Maya specialist Felix Kupprat at Mexico's National Autonomous University, also part of the study team. INAH added that the new imaging will better inform conservation as well as future field archeology at the site, which will likely see more tourists.

The study comes as Mexico's government has fast-tracked the construction of a multibillion-dollar tourist train to boost visits and promote development across the archaeologically rich but poor Yucatan region.