© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

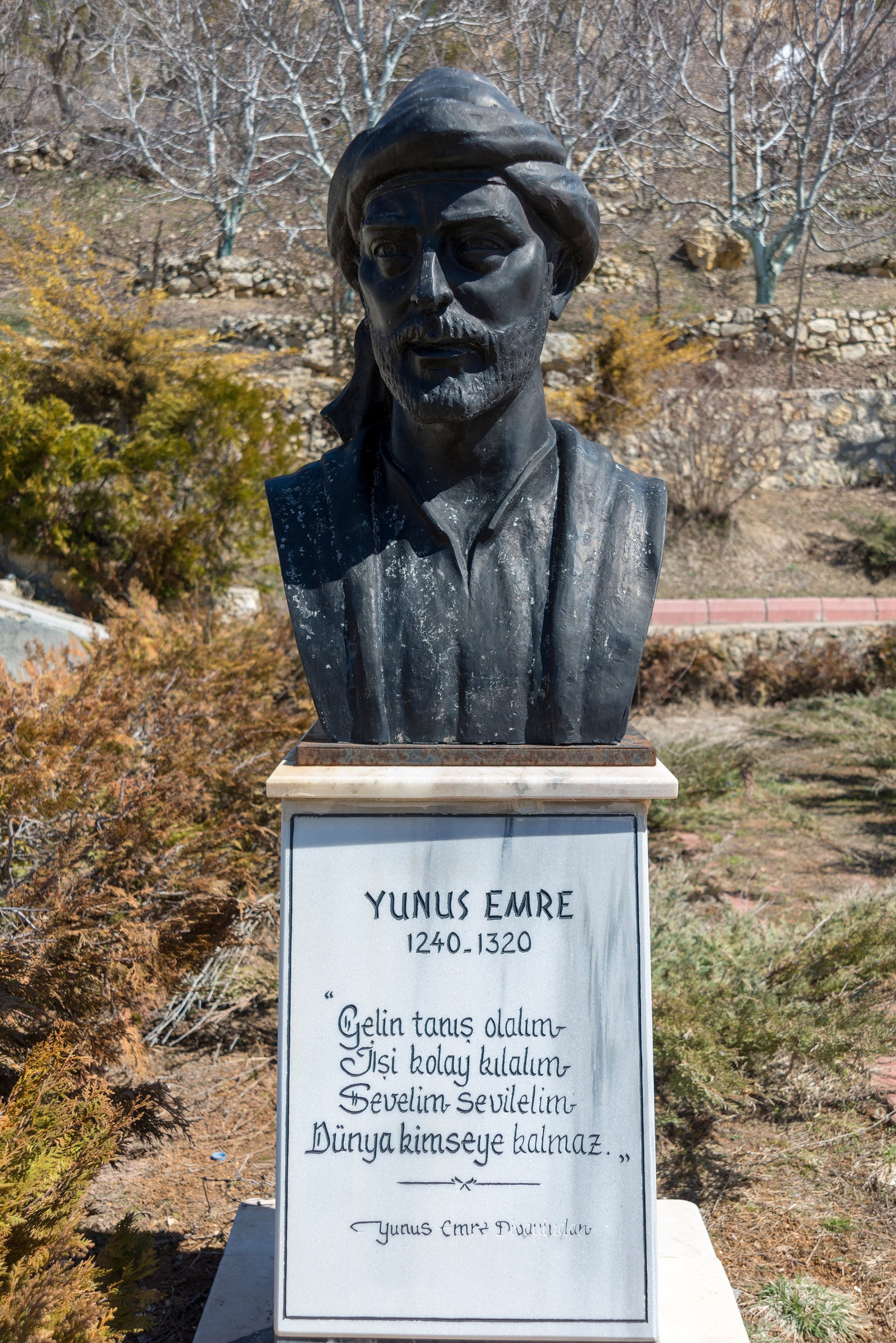

UNESCO has dedicated the year 2021 to Ahi Evran (founder of the Ahi order), Yunus Emre and Hacı Bektaş Veli. 2021 is the 700th anniversary of Yunus Emre’s passing while it is the 750th anniversary of Hacı Bektaş Veli’s death. It is also the 850th birthday anniversary of Ahi Evran. Therefore, various activities and projects to introduce these wise men of Anatolia are in the process of being implemented.

The reason for 2021 being the year of Yunus Emre and Hacı Bektaş Veli is related to a rumor about the lives of these two figures. According to the rumor, Hacı Bektaş Veli met with Yunus Emre and, following the events that developed between them, guided him to his student named Tapduk Emre. Some interpret this event symbolically.

Yunus Emre is the subject of many rumors, who during his life became a somewhat mystical persona as a traveling Sufi. Just like yeast melting in the dough and giving it flavor, he melted into Anatolian culture and became a spiritual architect in these lands. He was one of the figures that made up the spiritual and intellectual basics of Anatolian Islamic understanding.

Some say that there were many poets of the same name around before the 20th century and that the Sufi traveler Yunus Emre was the union of these different poets. More and more research was done on the thinker-poet after UNESCO declared 1991 the Yunus Emre Year of Love. The ambiguous information about his birth and death disappeared with a manuscript in the Beyazıt State Library in Istanbul’s Fatih district. It was recorded in the document that Yunus Emre was born in 1240-41, lived for 82 years and died in 1320.

Since the '90s, Yunus Emre's "Diwan", a collection of poems, has been considered his most important work. The most detailed study about Yunus Emre was published by Turkish-Islamic Literature researcher Professor Mustafa Tatcı as a critical edition. Thanks to his work, we now know which poems were penned by Yunus Emre, and which weren't.

Along with his poems, Yunus Emre is also most remembered for his “Risaletü'n-Nushiyye” (“Book of Counsel”). Researchers examining this piece of work and his “Diwan” consider him one of the greatest poets of the Turkish language. However, Yunus Emre legacy is not just that of a folk poet as he was also considered a deep intellectual and spiritual leader. Therefore, introducing the esteemed figure to the people of today is also of great importance.

In order to understand Yunus Emre, it is necessary to first dive into the world he lived. Anatolia was in a state of both material and physical exhaustion during the 13th century. Turkmen tribes escaping from Asia due to the Mongol invasion took shelter in the Sultanate of Rum (1077-1308). But they could not withstand the attacks too long.

After the Sultanate of Rum was defeated by the Mongol Empire in the Battle of Köse Dağ (a mountain between the present-day eastern cities of Sivas and Erzincan) in 1243, political unity was shattered. Mongolian cavalries entered every single town and city in Anatolia, crushing and fragmenting the country. The powerful had the last laugh in this miserable age filled with the clashes of swords and shields. It was a turmoil in which the strong, not the right, won; the scales of justice overbalanced and the power holders proclaimed their judgment.

The situation triggered plundering and famine. The land could not be cultivated properly, so crops could not be grown. The strength of the small principalities was also not enough to suppress the banditry in the villages. The people were tired and struggling to survive. Naturally, much of what was learned was lost due to the situation as many schools and artifacts belonging to the Anatolian Seljuk period were destroyed.

Within the turmoil, a voice stating "what a problem this is, there is no cure for it" started to rise. This voice from the heart of Anatolia belonged to Sufi traveler Yunus Emre. Just as the wood that Yunus Emre collected for his teacher Tapduk Emre's lodge for 40 years helped bake bread, the conversations Yunus Emre had with the teacher would help mature him.

When his teacher noted that Yunus Emre had brought back branches to use as kindling that was all straight and asked: "Is there no crooked wood in these forests?" Yunus Emre famously replied: "This place is such a gate of God and righteousness that no crooked man enters here, not even a crooked wood."

Having hit the road after the death of his teacher, Yunus Emre traveled a wide geography including Konya in Anatolia, Damascus in today’s Syria and Azerbaijan. There are also rumors that he met with his contemporary, great Sufi Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi. He completed his journey by returning to Sarıköy village, where he was born. Sarıköy, which is located in modern Turkey’s Eskişehir province and was is called Yunusemre village today, is at the junction of Porsuk Creek and Sakarya River.

In 1970, a mausoleum was built at his burial site according to rumors in Sarıköy. The fact that his grave is speculated to be all across Anatolia is a testament to the love felt for him. People often constructed monuments in his honor in places he had visited or passed through.

“Gönül” is at the center of Yunus Emre's poems. With its literal translation, gönül means heart. However, this word does not refer to a piece of flesh; it is a power in the heart and regarded as the center of the soul in Sufi literature. All feelings and thoughts, including the mind, are connected to it, the center of love. Just as the heart pumps blood around the body, everything in the “gönül,” including love and hate, spreads to the soul of the person.

This is not actually a metaphor. Prophet Muhammad explains it in many hadiths. That's why Yunus Emre puts the heart and soul together in the center of his poems. For example, in one of his poems, he says: “Knowledge means to know yourself, heart and soul.” In another verse, he also says "I did not come to fight, my work is with love. A heart makes a good home for a friend, I've come to mend hearts.”

Therefore, his pure, sincere and affectionate poems from his heart touched others. His poems were not limited to his own time and place. He deeply influenced thousands of intellectuals and artists. Thus, the depleted sense of spirituality of the Anatolian people was revitalized through the way of thinking he put forward.

Transferring his thoughts through Turkish poetry, Yunus Emre fundamentally shaped the understanding of both folk literature and the classical Ottoman literature called "divan literature." The words and expression patterns he uses as well as the meanings and metaphors he attributes to them helped propel Turkish to being classified as a literary language.

While many of his poems are simple and understandable, some feature symbolism and use literary tools like contrasting phrases. Poetry with implicit meaning was called "şathiyye," a common feature in Oriental literature and was reflected in Yunus Emre's poetry, too.

Topics that cannot be understood by everybody or prone to misunderstanding are conveyed in a language that only those who know those subjects can understand. Thus, thoughts or feelings are conveyed without confusing people. What he expressed in these poems was analyzed by Sufi scholars over the subsequent centuries.

In order to understand Yunus Emre's poems correctly, it is necessary to understand Sunni Islam, which is far from the moderate Anatolian Islam, in addition to the period he lived. In short, this is a form in which both the basic conditions of religion, called "zahir" and the moral and conscientious conditions called "batin", are combined in one pot.

In one of his poems he says "if you broke your heart once, this is not the prayer you perform.” In another verse, he says "whoever does not pray, he does not become like a Muslim". The poet, who invited humanity to remember and love Allah, frequently dealt with the subjects of death and the afterlife, mortality, immigration, poverty and dervishes in his poems. Divine love was the subject he dealt with the most.

According to him, love is above all. He says: “A person whose heart does not beat for Ar-Rahman (one of the 99 names of Allam meaning “the most merciful”) is like a town that has not become prosperous. Love matures, saves one from fears, cleans the soul by neutralizing the desire (egoistic requests).” According to him, every particle in the universe is a reflection and proof of God's attributes.

In fact, Yunus Emre wants neither the world nor the afterlife. He ruminated on the divine but the concept of death was strongly rooted in the thinker's mind. Yunus Emre shared the same philosophy as Rumi, that death is nothing but "meeting with the lover," thinking of it not as extinction but as a rebirth in the realm of eternity.

Despite his beliefs, he never broke ties with the world. According to him, Islam and Sufism do not represent the philosophy of “a bite, a cardigan," or hold a certain attitude towards the world order and structure. It means not to be enchanted by the world's blessings. Everything should be interconnected and in harmony and that man should fulfill his worldly responsibilities. It is harmful if goods, property and gold (money) are in the heart, rather than the purse.

According to him, everything, including death, is valuable and beautiful in its own place and in its own time. For example, he writes for those who died young:

“To one thing in this world

I am heart-stricken, my soul writhes in pain

That is the ones who died at a young age

Like the harvest of green grain.”