© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

It is rare, or unprecedented, for anglophone readers to find a comprehensive study of cultural artifacts conceived and exchanged across some of the most politically sensitive zones in world history. In particular, the swath of land encompassing the Middle East, Central Asia, the Balkans, the Levant and Mesopotamia, where local ruins, peoples and traditions have told stories of annihilation, conquering and perseverance since time immemorial. The reasons are many and include everything from postmodern colonialism to natural age.

Within her broad foundation of object-based research, Amanda Phillips is an intersectional art historian of those pasts where earlier forms of multiculturalism engendered anomalies and hybrids of plural human expression, further decentralizing the fringes of Western categorizations of department and discipline. Yet, steadfast in the face of her decidedly venturous approach, Phillips has published a number of frank, well-evidenced proposals throughout her dense book that might upend the historiography of cultural work produced on that cusp when medievals became moderns.

The upsurge of the Ottoman dynasty serves as the focus of Phillips’ remit, encompassing the years from 1200 to 1800, with significant concluding notes relevant to the current milieu. The geographies under question and the spheres of influence by their leading societies existed beyond the pale of European Christendom and were strained through assumptions of classical philosophy largely via Arab Muslim exegetes whose dominance preceded that of the Turks having land and title throughout Anatolia.

The prevailing sociocultural context in which Ottoman society developed would be largely unrecognizable to a person today. Specifically, its leaders had an entirely alternate set of beliefs and tastes with respect to images and text than that which forced its way up to the current model of global primacy as prescribed by the traditionally Christian nexus now generally termed the West, whose seafaring occupations gained irreversible traction over leading international markets by the 18th century.

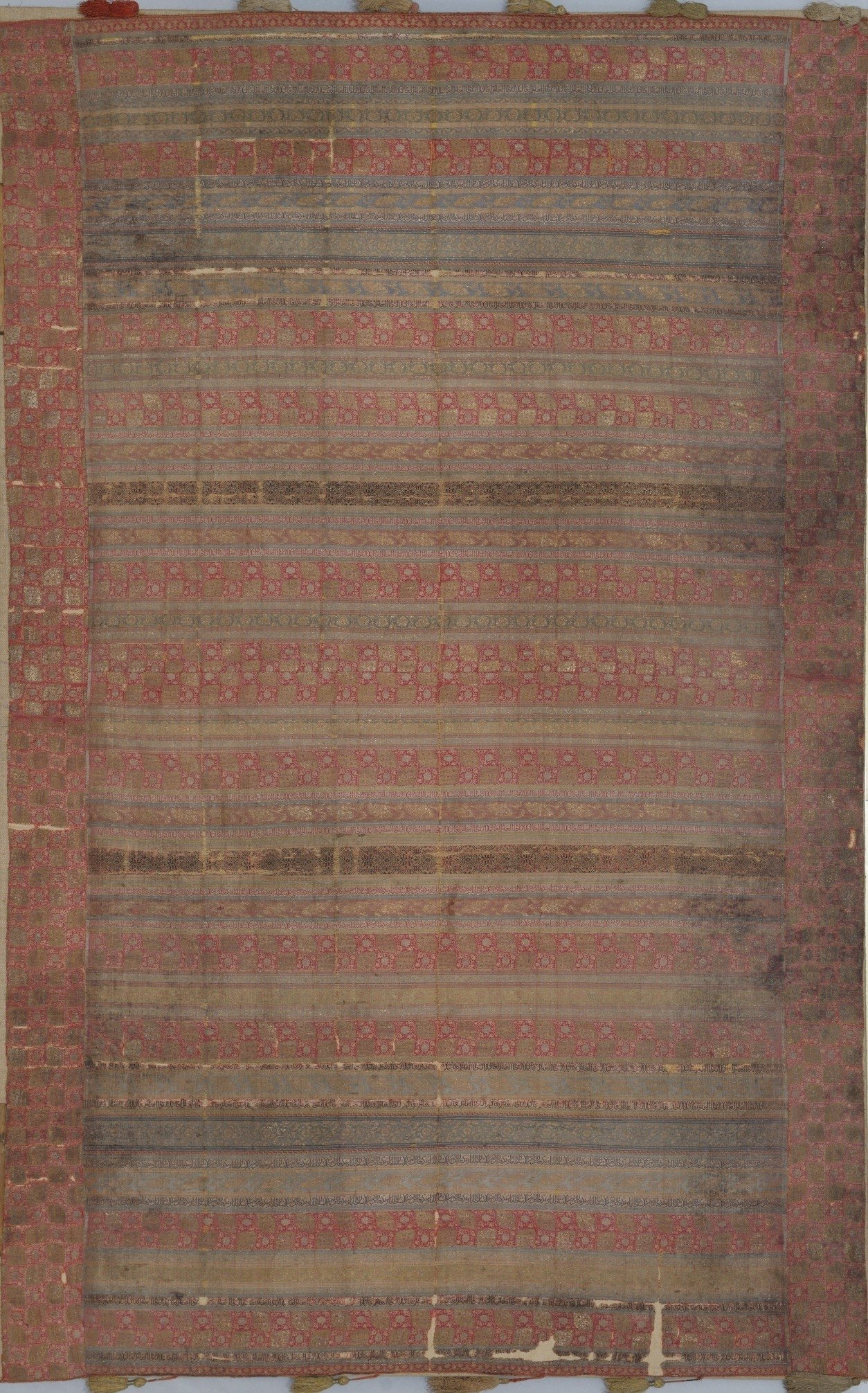

Together with changes in technology and the subduing of mass workforces from the Indian subcontinent to the American hemisphere, the colonial empires of Western Europe were achieving supremacy one piece of clothing at a time. But while wearable garments may have transformed to befit trends of the West – in some cases retaining eastward elements, particularly in the Balkans – certain customs fell through the cracks of such epochal change. Textiles for ritual, decoration and everyday use are a distinctive, and potentially all-important key by which to unlock the Ottoman world for the contemporary historical imagination.

In retrospect, the primary role that figurative, mimetic imagery plays in modern culture was not a foregone conclusion in the Middle Ages. Early art history is popularly dominated by religious scenography and famous portraits before artists experimented with models who could remain nameless, as the creative class came to control capital enough to commission painters to make art for art's sake. However, at the same time, the vast Asian continent had been shaped by another kind of artwork, one laden with precious metals and stitched with images less given to realism. This was due to the nature of its fundamental material – textile.

It is interesting to view the Ottoman industry of textile production through the lens of art history. For one, the objects were heavy with real value – arguably less abstract than currency – given that techniques of gold and silver thread were central to textiles. In the latter years of its trade as a mainstream commodity, when poorer members of society were both producing and consuming traditional Ottoman textiles, the materials came to assume the appearance of what had become a culture of decadence. The economic history of Ottoman textiles cannot be deemphasized in relation to Western definitions of art and wealth.

If the value is the result of that which is tradable, how tradable a commodity is is paramount to defining its value. For much of the textual investigation that informed her book “Sea Change: Ottoman Textiles between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean,” Phillips pored over contractual agreements listing the qualities and attributes of textiles as exchanged between buyers and sellers, who typically belonged to the heights of social status, with a formidable trove of palace records showing just what each sultan acquired. She found that the workers themselves kept worse records, if they did at all, likely a result of illiteracy in a multinational empire where, to many, public education was a foreign import.

To close the wide, and often vague gaps in knowledge between academic reference and the object-oriented scholarship of her methodology, Phillips examined minutes from the Shariah courts that presided over the legalities of textiles. Among these are the sumptuary laws that draw interest for the exoticism of its enforcement in comparison to the myths of personal freedom enjoyed by the West. These regulations – which arranged the wearing and prohibition of clothes according to people’s religion, gender, class, ethnicity and work – are a vital source for researchers interested in understanding the ways in which textiles established social codes prior to the introduction of concepts pertaining to modern identity and its salience in politics and government.

Throughout her book, Phillips highlights and chronicles a key point in her argument that textiles represent their own historiographic source material. A crucial support to her findings is the fact that the only commodity traded more than textiles in world history is grain. That their significance is underestimated by westward-thinking art historians is a wide gap in scholarship, which "Sea Change" begins to fill with clear delineations of prose offering readers meticulous insight into the pragmatics of the textile craft and the inspirations of its creative flourishing across classes and cultures.

Even a more astute reader will be glad for the comprehensive glossary, which includes designations common to the field, such as “sericulture,” to more obscure classifications such as a variety of lightweight silk known by the Turkish appellation “bürümcük.” Each chronological section in "Sea Change" is prefaced by epigraphs prior to Phillips’ clarifying texts accounting for themes pertaining to technology, terminology, style, production, regulation, consumption, imitation and novelty. The first chapter begins with a Turkish proverb that also serves as an apt metaphor for the writing process: "With patience, the cocoon on the mulberry leaf is made into a silk dress.”