The exhibition 'Opus II – Fantasia,' curated in-house at Arter by Emre Baykal, is an act of cultural revitalization in the name of Turkish art history meant to prompt a harmonious vision of retrospective contemporaneity

The abstract painter Agnes Martin saw the subtle gradations of color on her canvases as a kind of musical expression. Like notation, her process included a mathematical complex of proportional inventions by which she would bring the image that had come to her mind into the sensual world of painted space. When critiqued, she defended her almost opaque minimalist abstractions as the "pure emotion” of music, against the explanatory demands that were largely made in the name of contemporary art’s status quo intellectuality.

Perhaps similarly, the art of Füsun Onur is presumably a provocation of tonal visuality, of harmony, dissonance, rhythm and melody, however unstrung and unsung. That much is clear by the texts of Emre Baykal’s curation of her show, "Opus II – Fantasia,” a remount from 2001 titled after terms of classical composition, the first of which identifies a separate piece, often dated according to its publication, followed by a genre of free form improvisation enjoyed by almost every important composer since the Renaissance.

The works are placed in a spare configuration that might tickle the fancy of such object-based musicological artists of the Fluxus persuasion as curated by Melih Fereli in other shows at Arter, such as, "For Eyes That Listen.” What comes to mind, most popularly, are the calligraphic and nonlinear measures of notes by John Cage, reminiscent of surrealist collage, their indications of sound as texturally interpretive as they are invitations to perform on readymade instruments.

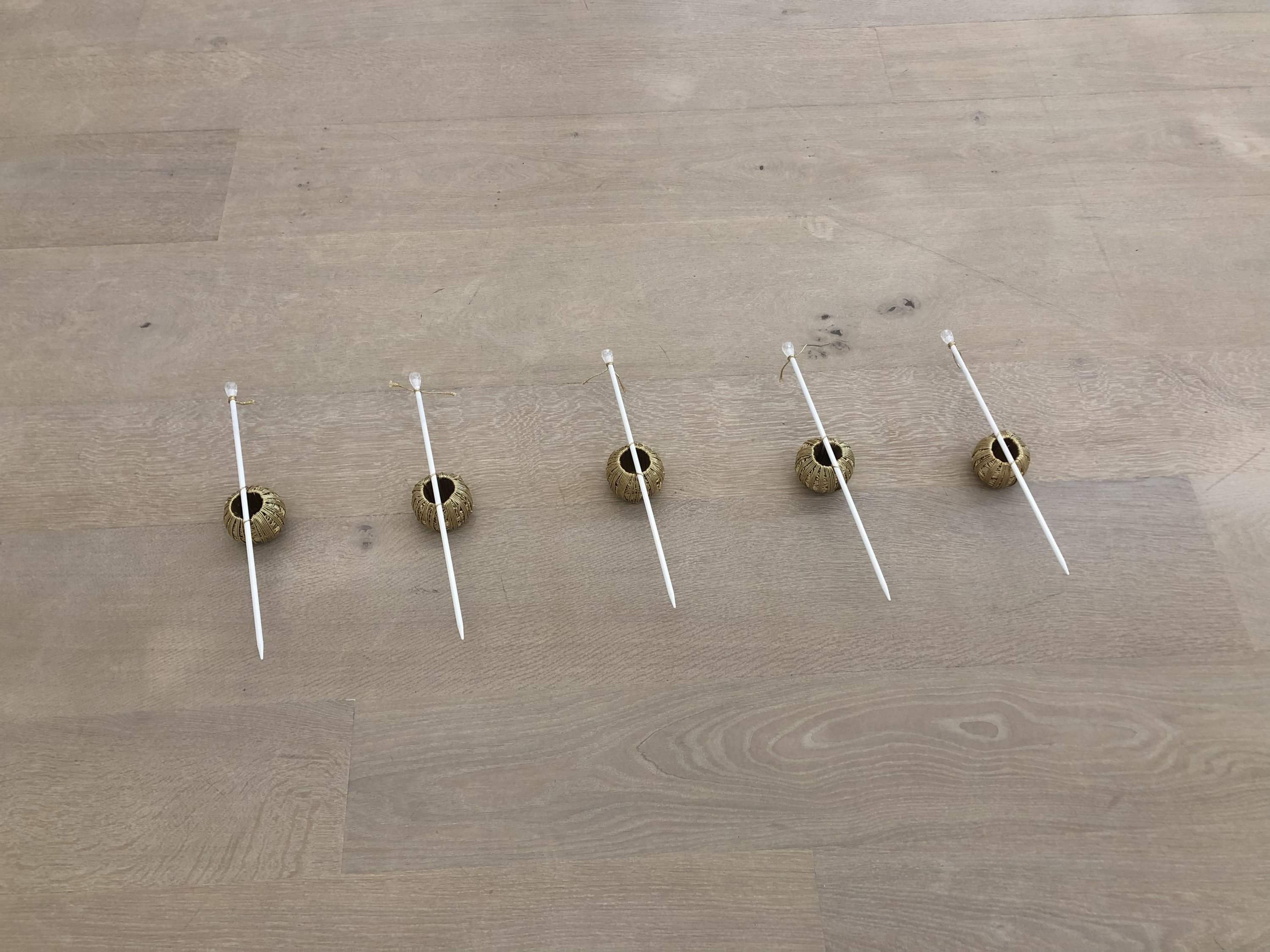

Distilled to very few shapes and materials, "Opus II – Fantasia” has a mirror effect against the whitewash museum gallery halls in which it is meticulously situated. A series of rectangular plinths, for example, almost exactly matches that of Arter’s interior architecture. Then, arrangements of knitting needles are spread across the floor in neat displays, like that of checked lines, a semblance of diatonic fifths. The reappearance of balls of gold braid is as mystifying as the miniatures of delicate porcelain figures standing on the clean wooden floors.

Of the shore and city

Onur, born in 1938, is a relic of the old guard among Turkey’s critical art historians. Bursting onto the international art scene fired by the singular flame of her worldview as a Turkish woman of the late 20th century, couched in an upper-class, westward gaze, fresh from the estuarial climes of the Chesapeake Bay as a graduate of Maryland College of Art, she returned to Turkey in the early 1970s.

Inspired by her worldly vistas, she started working from her childhood home in the Bosporus neighborhood of Kuzguncuk, its breezy airs giving her just the perspective she needed to reflect on the role of sculpture in a country where public space and contemporary art were contested by the eternal dramas of human tragedy. She would sip her tea under a swaying plane tree and contemplate her capacity to transform Istanbul itself as sculptural expression.

And looking out over the Bosporus from her pacific nook, eyeing such splendors as Dolmabahçe Palace, she knew that she would have a hand in transforming their procession through the blank canvas where history and the future met at the confluence of the present. Such backstories are integral to "Opus II – Fantasia,” as an adjacent room on the floor of the main exhibition offers ample reading material about the artist’s long life and prolific works.

In 1977, she developed her approach to site-specificity on the exquisite grounds of Dolmabahçe Palace. But it was Istanbul’s local art world, namely Maçka Sanat Galerisi (translated as Maçka Art Gallery), where she found room to test her artistic explorations into the spatiality of music, namely with shows like, "Cadence” (1995) and "Prelude” (2001). Ultimately it was Germany’s Kunsthalle Baden-Baden that first showed "Opus II – Fantasia.”

And once landed

Risen amid the decadent glitz of early republican Turkey’s so-called golden age in which the late imperial upper class had yet to fully merge into meritocratic, middle-class democracy, the timing of Onur’s career is essentially on the cusp of classist issues in relation to art history in Turkey as its leading creatives broke ranks with Orientalist Francophiles and made way for the ongoing path toward its universalization, not without a few pebbles, or boulders, in the way. And even in a European context, her art seems to maintain her rarefied neo-bourgeois enigma.

The 2021 revitalization of "Opus II – Fantasia” is not different. It does not appear to be concerned with prompting a new vision of intelligent, emotional communication with seers who might immerse themselves in her mysterious, repetitive aesthetic of curiously concerted objects entwined into utterly silent, spatially imbued metaphors for music. Without reference to her oeuvre, especially works like "Blue Counterpoint with Flowers” (1982) or "Dividing the Space on a White Piece of Paper” (1966), "Opus II – Fantasia” is painfully aloof.

In the interest of canonizing luminaries of Turkish contemporary art anew, "Opus II – Fantasia” resounds at Arter with the impressionistic euphony of its curatorial thematics, pleasant and mellifluous as the clarity of its accented emptinesses. But it is also an agonizing, self-absorbed haute design for those among the culturati familiar with the unsaid mimesis of their perfectly bubbly socioeconomic classism. When reconsidering the idea of the national canon while simultaneously striving for domestic and global relevance, there are apt to be pitfalls.

In a booklet insert printed with the catalog for Onur’s past solo exhibition in Istanbul, "For Careful Eyes,” featuring the writing of Margrit Brehm, Baykal wrote a brisk essay titled, "An Afternoon with Füsun and Ilhan Onur” in which he described his visit to their quaint home in Kuzguncuk. In fact, his descriptions are meticulous, down to the "porcelain plates, embroidered tulle curtains, needlework covers, this is a living museum,” he wrote. Onur told him that her father encouraged her to pursue art because he failed to succeed in it.

It was March of 2007 when Baykal wrote of her for the Yapı Kredi Publications book, and her portrait, while still elegantly beautiful, had aged her well apart from her prime in the 1970s, when she was one of Turkey’s foremost art stars inheriting the spectacular pride that had lionized the likes of Fahrelnissa Zeid and Füreya Koral. Her unfading prominence is more a cause for wonder now than celebration, and rightly so, as "Opus II – Fantasia” is less like the inescapable charm of music but an unplayed sheaf of sheet music being passed around to a tone-deaf audience.