© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

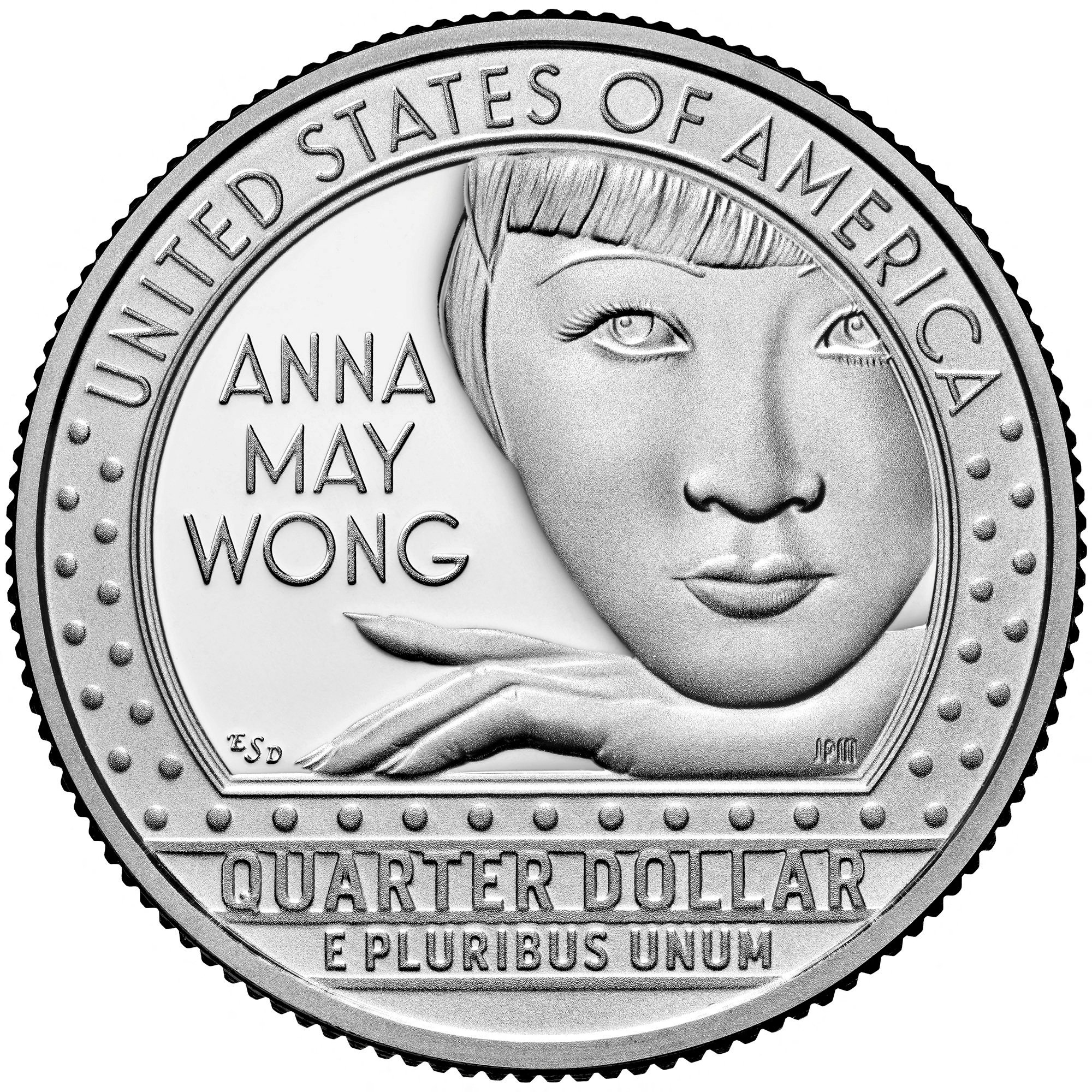

More than 60 years after Anna May Wong became the first Asian American woman to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the pioneering actor will feature an Asian American on U.S. currency for the first time.

Wong, who fought against stereotypes foisted on her by a white Hollywood, is one of five women being honored this year as part of the program. She was chosen for being “a courageous advocate who championed for increased representation and more multi-dimensional roles for Asian American actors,” Mint Director Ventris Gibson said in a statement.

The other icons chosen include writer Maya Angelou, author and civil rights champion, Dr. Sally Ride, an educator and the first American woman in space, Wilma Mankiller, the first female elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and Nina Otero-Warren, a trailblazer for New Mexico’s suffrage movement.

Wong’s achievement has excited Asian Americans inside and outside of the entertainment industry.

Her niece, whose father was Anna May Wong’s brother, will participate in an event with the Mint on Nov. 4 at Paramount Studios in Los Angeles. One of Wong’s movies, “Shanghai Express,” will be screened, followed by a panel discussion.

Arthur Dong, the author of “Hollywood Chinese,” said the quarter feels like a validation of not just Wong’s contributions, but of all Asian Americans. A star on the Walk of Fame is huge, but being on U.S. currency is a whole other stratosphere of renown.

“What it means is that people all across the nation — and my guess is around the world — will see her face and see her name,” Dong said. “If they don’t know anything about her, they will ... be curious and want to learn something about her.”

Born in Los Angeles in 1905, Wong started acting during the silent film era. While her career trajectory coincided with Hollywood’s first Golden Age, things were not so golden for Wong.

She got her first big role in 1922 in “The Toll of the Sea,” according to Dong’s book. Two years later, she played a Mongol slave in “The Thief of Bagdad.” For several years, she was stuck receiving offers only for femme fatale or Asian “dragon lady” roles.

She fled to European film sets and stages, but Wong was back in the U.S. by the early 1930s and again cast as characters reliant on tropes that would hardly be tolerated today. These roles included the untrustworthy daughter of Fu Manchu in “Daughter of the Dragon."

She famously lost out on the lead to white actor Luise Rainer in 1937′s “The Good Earth,” based on the novel about a Chinese farming family. But in 1938, she got to play a more humanized, sympathetic Chinese American doctor in “King of Chinatown.”

The juxtaposition of that film with her other roles is the focus of one day in a monthlong program, “Hollywood Chinese: The First 100 Years,” that Dong is curating at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles in November.

“(‘King of Chinatown’) was part of this multi-picture deal at Paramount that gave her more control, more say in the types of films she was going to be participating in,” he said. “For a Chinese American woman to have that kind of multi-picture deal at Paramount, that was quite outstanding.”

By the 1950s, Wong had moved on to television appearances. She was supposed to return to the big screen in the movie adaptation of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Flower Drum Song” but had to bow out because of illness. She died on Feb. 2, 1961, a year after receiving her star.

Bing Chen, co-founder of the nonprofit Gold House — focused on elevating representation and empowerment of Asian and Asian American content — called the new quarter “momentous.” He praised Wong as a star “for generations.”

But at the same time, he highlighted how anti-Asian hate incidents and the lack of representation in media persist.

Asian American advocacy groups outside of the entertainment world also praised the new quarters. Norman Chen, CEO of The Asian American Foundation, plans to seek the coins out to show to his parents.

“For them to see an Asian American woman on a coin, I think it’d be really powerful for them. It’s a dramatic symbol of how we are so integral to American society yet still seen in stereotypical ways,” he said. “But my parents will look at this. They will be pleasantly surprised and proud.”

To sum it up, Chen said, it’s a huge step: “Nothing is more American than our money.”