© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Two hundred years ago, as Ludwig van Beethoven's majestic Ninth Symphony echoed through the halls of a Vienna concert venue, the esteemed German composer felt a surge of anxiety, hoping for a flawless performance.

He needn't have worried. The audience erupted in spontaneous applause during the performance, but Beethoven was already so hard of hearing that he had to be turned around by a musician to notice it.

While he was born in Bonn in 1770, Beethoven spent most of his life in Vienna after moving to the Austrian capital as a 22-year-old.

Despite receiving repeated offers to relocate, the legendary composer never left Vienna, where he had found his home, surrounded by supportive fans and generous patrons.

"It was the society, the culture that characterized the city that appealed to him so much," said Ulrike Scholda, director of the Beethoven House in nearby Baden.

The picturesque spa town just outside Vienna deeply shaped Beethoven's life – and the last symphony he would complete, she said.

"In the 1820s, Baden was certainly the place to be," with the imperial family, the aristocracy and a who's who of cultural life spending their summers there," Scholda said.

Beyond his hearing loss, Beethoven suffered from various health problems ranging from abdominal pains to jaundice and regularly went to Baden to recuperate.

Enjoying long walks in the countryside and bathing in Baden's medicinal springs helped him recover while simultaneously inspiring his compositions.

In the summers leading up to the first public performance of his Ninth Symphony in 1824, Beethoven stayed at what is known as Baden's Beethoven House, which now serves as a museum.

It was there that he also composed important parts of his final symphony.

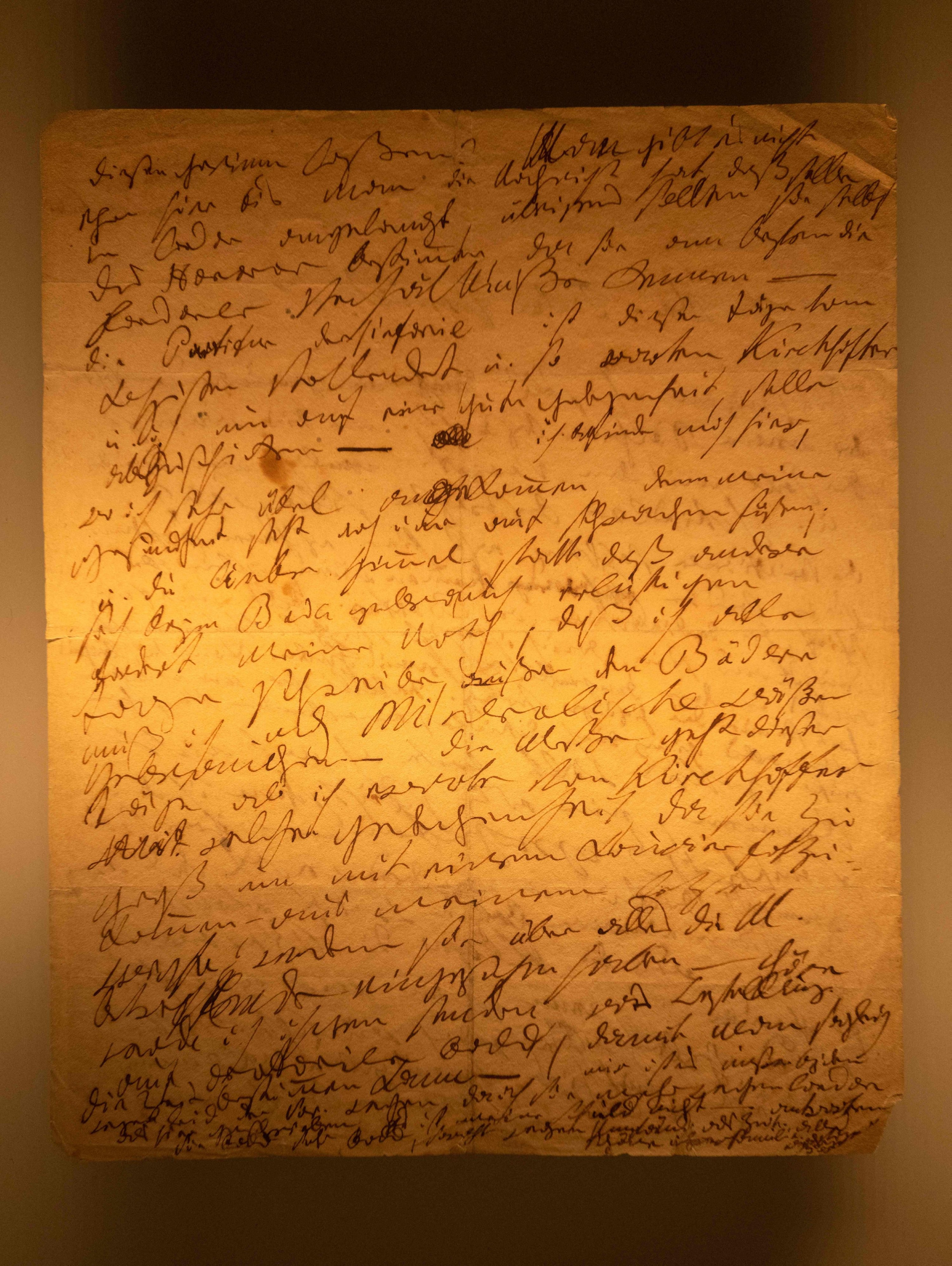

A letter Beethoven sent from Baden in September 1823 details the pressure he felt to finalize the symphony to please the Philharmonic Society in London, which had commissioned the work, Scholda said.

After completing the symphony in Vienna, weeks of intense preparations followed, including an army of copyists duplicating Beethoven's manuscripts and last-minute rehearsals culminating in the premiere on May 7, 1824.

The night before, Beethoven rushed from door to door by carriage to "personally invite important people to come to his concert," said historical musicologist Birgit Lodes.

He also managed to "squeeze in a haircut," Lodes added.

At almost double the length of comparable works, Beethoven's Ninth broke the norms of what until then was a "solely orchestral" genre by "integrating the human voice and thus text," musicologist Beate Angelika Kraus told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

His revolutionary idea to incorporate parts of Friedrich von Schiller's lyrical verse "Ode to Joy" paradoxically made his symphony more susceptible to misuse, including by the Nazis and the Communists.

The verses "convey a feeling of togetherness, but are relatively open in terms of ideological (interpretation)," Kraus said.

Since 1985, Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" from the fourth movement has served as the European Union's official anthem.

Outside the Beethoven House in Baden, which is marking the anniversary with a special exhibition, visitor Jochen Hallof said that encountering the Ninth Symphony as a child had led him down a "path of humanism."

"We should listen to Beethoven more instead of waging war," Hallof said.

And on Tuesday night, that certainly will be the case, with Beethoven's masterpiece reverberating throughout Europe with anniversary concerts in major venues in Paris, Milan and Vienna.