© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

On sunny days, natural light pours into the Beaux-Arts facade of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and bounces off the white marble of ancient Greek statues. Young artists patiently sketch the immortal contours in the undying tradition of mimesis as millions of curious eyes wander past in the search of visions that, whether made in the last month or 5,000 years ago, may change them for a lifetime, fulfilling the great human need to exercise the aesthetic mind.

In his peerlessly inventive lectures, the comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell would echo the words of California poet Robinson Jeffers when defining that sensibility that is shared across cultures, and that has separated man from beast since the dawn of time. He called it, "superfluous beauty," or, that which is not necessarily necessary, and by virtue of that mysterious, contrasting quality, exudes a beauty that is divine, or simply, extraordinary.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has ever had close relations with the Islamic art world, beginning the decade prior to its opening in Central Park in 1880, where it stands. Two years before the Ottoman Empire leased Cyprus to the British Empire in 1878, while remaining under Turkish rule de jure, the American consul Luigi Palma di Cesnola finalized the purchase of a vast collection of antiquities, now celebrated as the Cesnola Collection of Cypriot Art.

Much of his collection, going back to the Bronze Age, is housed in the second-floor sections for Greek and Roman Art. Its halls neighbor a span of works from Islamic civilizations, namely, Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and Later South Asia. In one corner, through a contiguous web of interconnected rooms lavished with an impressive scope of artistic traditions crafted by Muslim hands is The Decorated Word.

A shared faith in language

Of the nearly 50 pieces on display for The Decorated Word, subtitled, "Writing and Picturing in Islamic Calligraphy," there are four modernist pieces, all by Iranian artists, and made within the last half-century. "Untitled" (2013) by Golnaz Fathi reimagines the look of calligraphy. She uses the visual vocabulary of an abstract expressionist, inspired by the spontaneous scratches of the seismograph, and electrocardiograph.

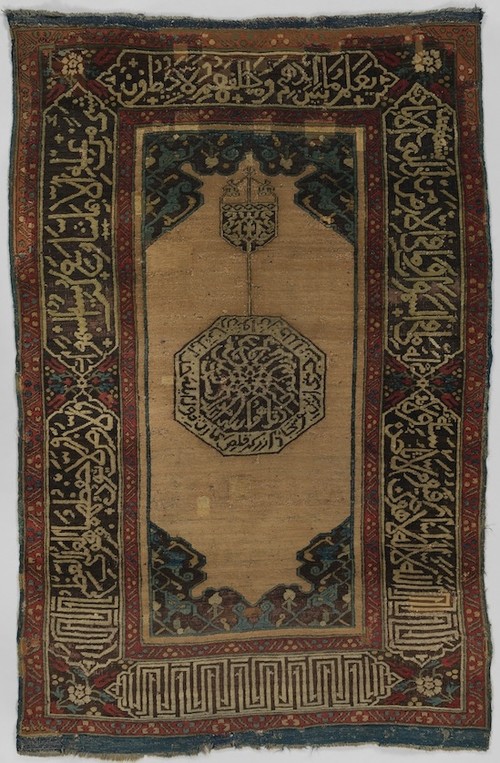

Carpet with pseudo-kufic inscriptions, Turkey, probably 17th century, wool (warp, weft and pile); symmetrically knotted pile.

Golnaz, whose works have appeared in Istanbul, quotes art history liberally. The curators of The Decorated Word at The Met identified her patterns as aligning to the "flung ink" styles of Japanese and Chinese calligraphers, also the action painting of Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline. In her meticulously visioned mashup of acrylic, pen, and varnish on a diptych of two canvases, Golnaz presents a surreal landscape of mirrored mountainous lines, starry cloudbursts of black.

The centerpiece of the show is contemporary, emphasizing the inspired perpetuity of the art of calligraphy from the Islamic world, and its ongoing universal appreciation. A bronze statue titled, "Poet Turning into Heech" (2007) by the Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli is in continuity with his creative practice. Tanavoli, born in 1937, has spent a great deal of his career in search of the shape of nothingness, embodied by its word in Persian, "heech" (like "hiç" in Turkish, meaning "nothing" in English).

"Poet Turning into Heech" is a play on the anthropomorphic form of the Persian word, "heech," rendered into a column of bronze. The word itself is contorted below a pillar engraved with pseudo-inscriptions in the Arabic script of the Persian language. In a single sculpture, Tanavoli manifested an aggregation of cultural expressions, from the prayer wheels of Tibet to the stone tablets of Mesopotamia.

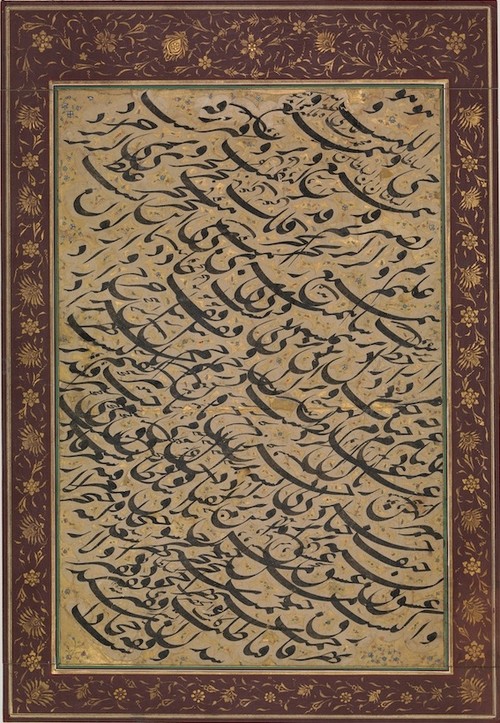

The late 20th century works of by the Iranian artist Faramarz Pilaram, titled, "Pair of Calligraphic Compositions" (1979) are in direct dialogue with a staple in calligraphy exhibitions, the exercise page, popularized as art since the 16th century. The purely visual effect instills what in Persian is referred to as the "siyah mashq" or literally, "black practice," in which overlapping words are encouraged for the calligrapher to isolate their subjective experience of the craft.

Album leaf with calligraphic exercise (siyah mashq), (1842–3) by Asadullah Shirazi, Iran, ink and opaque watercolor and gold on paper.

The orbital repetition of the words stacked on top of each other into an indecipherable mass directs the eye to see into the essence of calligraphy, which is to write words without a mind for their literal meaning, but instead, to focus exclusively on how they look. The historic calligraphy practice pages on display are from the mid-19th century, by Muhammad Shah Qajar and his court calligrapher, Asadullah Shirazi.

The art of Quranic script

In the Arabic script, there are six main, classical cursives, and two regional calligraphies. The "muhaqqaq" variation, literally meaning "clear," was long favored by the caliphates, particularly during the Mameluke era. The Ottomans tended to prefer other styles, such as "Thuluth" or "Naskh." The Decorated Word shows early Turkic usages of "muhaqqaq." One from the 14th century is from a Quran penned with interlinear translations into Persian.

The ink, gold and opaque watercolor leaps off the paper with an exacting freshness imbued with the eternal nature of its significance. While the calligrapher is not known, another piece at the exhibition from the late 14th century is identifiably the creation of one Umar Aqta from Samarkand. He inked a fragment of calligraphy for what was likely the largest copy of the Quran ever produced.

The legend goes that Timur, or Tamerlane to the West, received a miniature Quran written in the dust-like "ghubar" script by the calligrapher Aqta, but he disapproved. Aqta came back with a 7-foot tall Quran weighing half a ton, containing some 1,500 pages. The Met included a photograph of the monolithic marble Quran stand from the 15th century in front of the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Uzbekistan that held the massively oversized holy book.

The tale pivots the essence of calligraphy, which sees the sacred value of language as the vessel of divine intervention. Prophet Muhammad was illiterate, but he was not denied spiritual revelation, or what Buddhism terms "liberation through hearing." The Decorated Word states the centrality of the Quran as the prime muse for calligraphic art. Exhibited are parchments inked from the 9th to 10th centuries in the rudimentary "kufic" script.

The dust-like script of Umar Aqta's famous failed Quran was the chosen style of calligrapher Abd al-Qadir Hisari from Turkey, who decorated a prayer book. The Met itemizes the work in transliteration as du'anama, which, is based on the words "dua" or prayer in Turkish, and "nama" which means "epic" in Persian. The tiny calligraphic illustrations of Hisari suffuse Noah's ark, the Kaaba of Mecca, footprints of the Prophet Muhammad, and other iconic images. One of the more mesmerizing works at the show is a Turkish wool carpet dated from "probably 17th century." Its symmetrically knotted pile bears pseudo-kufic script. The curators included a photo of a 15th-century Italian painting from a tradition in European art that integrated pseudo-kufic script into haloes and the like for its refined airs.