© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

In Turkey, the small Jewish minority of some 20,000 people mostly speak Spanish, descending from exiles of the Iberian Peninsula who received an invitation from Istanbul's second sultan, Beyazid II, to settle in what was then a flourishing and expanding Ottoman Empire. They emigrated en masse, most to Thessaloniki, following inquisitions that expelled them and their Muslim compatriots by the turn of the 17th century.

They never forgot the land they called Sepharad or the dialect they spoke, Ladino. In fact, Turkey is the last place in the world where Ladino or Judaeo-Spanish upholds its distinguished legacy in publishing, due to the efforts to the Ottoman-Turkish Sephardic Cultural Research Center, which globally distributes El Amaneser (The Dawn), a monthly supplement of "Şalom" (Shalom), the nation's Jewish newspaper.

In Istanbul, they met coreligionists whose second motherland after ancient Judea went by another name, Ashkenaz, a Hebrew term for the territory around the Rhineland valleys, mainly in Germany where they had lived since at least the beginning of the second millennium. Their tongue is a blend of High German, including notes of Aramaic, and Slavic and Romance loanwords. It is called Yiddish, which in Yiddish translates, simply, as Jewish.

For two thousand years, it was the lingua franca of European Jews, whose networks crossed imperial boundaries, sharing methods of communication and cultural codes across the breadth of the Western world for a millennium preceding the advent of modern nationalism. During the medieval era, when Latin was primary among the educated elite, the common speech of early Christians was often incomprehensible between neighboring villages.

But local Jews, the Ashkenazim as they are referred to in the Hebrew plural had uniquely coined methods of communication that were simultaneously integrated with the social majority, with whom they dealt, often as mercantilists, while retaining the exclusive color of their linguistic and cultural heritage. Unlike their distant cousins at the end of the Mediterranean in Spain, Istanbul was ever a crucial stopover for pilgrimaging Ashkenazis on the route to Jerusalem.

With faith in friendship

Schneidertempel, endearingly nicknamed the Tailor's Synagogue by its local community has held several exhibitions, from contemporary art to historical interpretation, along with events and talks in association with the Dr. Markus Arts and Cultural Association.

Its programs convey the unique perspective of its people, whose relation to the mainstream narrative of Turkish history was buttressed by the challenges and redemptions of pluralism.

From the piers on either side of the Galata Bridge in Karaköy, urban explorers are likely to climb the tulip-shaped weave of the Camondo Steps, its Neo-Baroque and Art Nouveau architecture attracting street musicians and footsore sightseers. Up from the fortified airs of the Avenue of Banks (Bankalar Caddesi), the elegantly constructed stairway was the vision of Abraham Salomon Camondo, an Istanbul native from a family of Jewish philanthropists.

Ascending the steep slope of the ancient Genoese city, leading under the 14th-century shadow of the Romanesque-style Galata Tower, the narrow Felek Street, named after the Turkish word for "fate," winds inward perpendicular to the unmistakable synagogue entrance facade of Schneidertempel. Its unsophisticated hall is characteristic of the relatively plain Ashkenazi ambiance, in contrast to the generally fancier decor of Mediterranean communities.

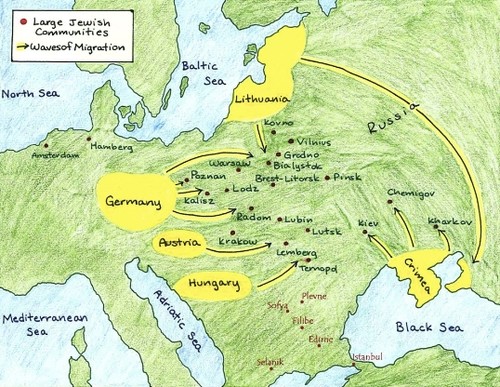

Ashkenazi communities and their migrations.

A single row of wooden benches is all that remains of the bygone congregation founded in 1894, only to close by the 1960s, awaiting its contemporary revitalization as a cultural center beloved by the children of its former members. Under a six-pointed star of window glass stained with effulgent hues of purple, blue, green, red, yellow and white, an antique candleholder is permanently displayed inside the now-empty ark of scrolls, evoking the spirit of remembrance.

An exhibition to remember

Outside the Jewish Museum of Turkey, which is decidedly Sephardic in orientation, Schneidertempel is exhibiting one of the most comprehensive histories of Turkish-Ashkenazi life ever assembled. In from the entranceway, rows of sepia-toned and black-and-white photographs revitalize the presence of Turkey's Yiddish-speaking Jews. Their children are in suits and dresses. Norbert Liberman smiles at his 13th birthday party, before his bar-mitzvah.

A picture shot in a studio in Pera shows the young family of Fritz J. Rozental seated, straight-faced, with two boys in sailor's outfits, and a daughter, around three years of age with a flower tied around her arm. Their faces are clear and expressive, the moment captured. All of history is reduced to an instant. Rows of children are lined by height on Kalamış, a summery sailing port in Istanbul facing the Sea of Marmara. It is 1927, as the Bornstein's make merry.

The album of the Bornstein family is remarkably revealing of the spirit of the age, during the heady interwar era after the struggle for world peace had been fought, and women were gaining freedoms, as were artists, thinkers and statesmen. Turkey was growing up. The children accompanied their joyful adults around a movable theater booth for Karagöz shadow puppetry. Three women in the photo look entirely liberated by the Roaring 20s, dressed fashionably.

100 Ukraine Karbovanets (Ukrainian, Polish and Yiddish) dated 1917.

The ground floor is relatively spare compared to the second story, where women would sit in the orthodox tradition, separated from the men praying below. The stairway up is marked with interpretive signage detailing the chronology of Ashkenazi history alongside milestones in the building of the Turkish nation, beginning from the 16th century. But it was a century earlier when Ashkenazis first settled in Ottoman lands.

Before the invitation of Beyazid II prompted the Sephardic exodus, the Ashkenazi Rabbi Isaac Tzarfati wrote a letter to his communities in Germany, Hungary and France. In 1492, Sephardic immigration further stimulated their fellow Jews of the north to prosper with them in the Ottoman Empire, what was then a richly opportune imperial sphere. With their institutions based in the Galata region of Istanbul, the Ashkenazim were well integrated by the 19th century.

Together with interpretive texts, glass cases of artifacts detail the life of the community, with such items as a shofar, a ram's horn blown to ring in the Jewish new year and the clothing of a cantor who would have used it, and his sheet music.

Unlikely finds include Ukrainian paper currency in Yiddish, and an Ottoman document registering a Hungarian synagogue in Şişhane, also the more standard Torah scrolls, birth certificates, prayer books and school papers.

The peculiar Ashkenazi sense of humor is not lost in Schneidertempel's curation. A series of cartoons by Irvin Mandel are shown with project advisory by Izel Rozental, also a cartoonist for Şalom, Turkey's Jewish newspaper.