© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

Although born in Istanbul, Gülay Semercioğlu describes herself as an Anatolian girl. Before moving to the shores of the Bosporus, her ancestors were raised on the buttery richness of the Gaziantep palate. But they never forgot their taste for its culinary landscape. Her parents still stock their spice cabinet and bread pantry with the ancient vinegar of its pickled vegetables, the dried skins of its searing peppers, and the mouthwatering glory of its honeyed pastries.

Now a mid-career artist, the metaphorical kitchen of her personal creative process also doubles as a place of cultural remembrance. At home in the techniques she has honed for nearly three decades, she continues to reflect on her peculiar emergence of art and craft by literally drawing alternate lines of practice, despite the prestige of her Westward-thinking education from the Painting Department of Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in the 1990s.

Mostly known for her knittings of reflective, metallic wire, which have entered some of the finest institutional collections of contemporary art around the world, she has finally unearthed the raw source of her skills as a draftswoman exclusively for her solo show, "Desire to Survive." The intricacy of her lines on paper has its visual parallel in her labor-intensive warp and weft of the textile aesthetic, with respect for varieties of patterning special to Turkish cultures.

A handmade woman

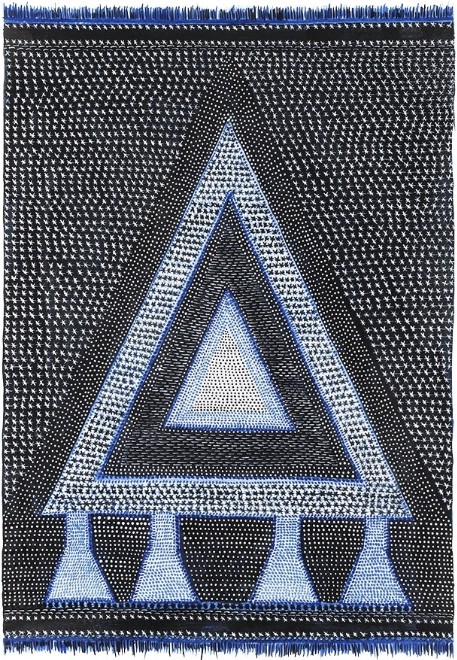

Her nuanced gradations of color, symbolic as they are photogenic, retain the mirror-like animation of her wire-based adaptations, changeable in response to the perspective of the seer. And the utilization of points and stars are transfixing, with perceivable equivalents in the fasteners and screws that she uses when knitting with metal. She quotes liberally from such traditions as Iznik tiles, Hittite goddesses, Ottoman octagons, Kurdish kilims.

One piece, titled, "Zilli" (2017), is compact at 30 x 21 cm, though it makes up for its scale with its minute detail, clearly the work of an obsessive perfectionist. Over her kitchen drawings, Semercioğlu devotes herself to a quality all her own, pushing the knife edge of familiar delights with individual originality. She is, in that way, like a fine dining chef who has replaced her ultimate goal of pleasing the tongue with a pure evocation of rapture through the eyes.

Among certain Buddhist faiths, such as is endangered in Tibet, the senses are mediums through which human beings may achieve spiritual freedom from the endlessly tempting cycles of creation and destruction. The art of the Thankga, often scroll paintings on cotton and silk, entrains the faculty of sight through higher planes of consciousness, toward a transcendent experience of what such wisdom practitioners have called liberation through seeing.

"Zilli," 2017, ink on paper, 30 x 21 cm.

Semercioğlu frequently refers to the aniconic prohibition in Islam, which, throughout its multicultural history, has, like orthodox Judaism, disallowed figurative illustration in the context of religious observance. What resulted is millennia of increasingly entrancing developments of geometrical patterns in the Islamic arts, in continuity with earlier Anatolian antecedents in the plastic disciplines of ceramics and sculpture.

The geometry of opposites

In both her drawings and wire works, Semercioğlu uniquely fuses two- and three-dimensional perception. "My Bloomy Lover" (2018) is a feast of tones, as its linear motifs follow progressions of repetition in harmony with the lightness and darkness of subdued shades of beige and gray in contrast to starry cores of blood red. The piece is enlarged, and shocked with a visceral vibrancy as "A Carpet of Red Flowers" (2018), handmade with wire, screws and wood.

"Hands on Hips - Power," 2018, ink on paper, 29 x 17 cm.

She is proud to be Turkish, because of her country's liminal self-definition in confrontation with its neighbors, as the eternal other always in search of its regional and global identities. Turkey is generally unaccepted as a full member of the East, or of the West. Its distinctive, Central Asian brand of Islam is commonly dismissed by the Arab world. And its exotic embrace of Western lifestyles is often tokenized by postcolonial European society.

But for Semercioğlu, marginality is an opportunity through which to embrace internalized opposition through creative pursuits. As in her work, "Zilli," and "Hands on Hips - Power" (2018), she is foregrounding the body of fertile women, central to the feminine goddess cults mythical to Anatolian prehistory. Its forms remain integral to the sacred geometry of what to a superficial mind would derogate the visual arts of patriarchal monotheist orientations to mere abstraction.

"My Bloomy Lover" excavates sculptural features of Anatolia's ancient feminist themes onto the flat surfaces of her ink drawings and wire textiles. As with "A Carpet of Red Flowers," she conveys the ram's horn, and female hips, as part of a holism observed by history's oldest civilizations. The comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell explained the shape of cattle horns as a primeval symbol of heaven on earth as the beasts drink dew under the crescent moon.

A legendary scholar who posited the prominence of ecological goddess cultures among prehistoric peoples throughout Eurasia, from Anatolia to the Scandinavia, was Marija Gimbutas. After researching the Neolithic era (7000 B.C. - 3500 B.C.), she coined the term, Old Europe, based on her discovering the existence of female-dominated theocracies, which were egalitarian, peaceful, and organized around matrifocal kinships.

In dialogue with the creator

As much as Semercioğlu is influenced by the anonymous ingenuity of her archaic heritage in Turkey, her education, and interests encompass Western art history, especially where the two have touched. For example, she considers the American abstract painter Frank Stella as a true visionary important for her artistic growth. Stella researched the geography of Kayseri, which he applied to his anomalous oeuvre, notably including the lithograph, "Turkish Mambo" (1967).

"At university I was using oil and acrylic. I wanted to be a sculptor. It was impossible to study sculpture and painting. I chose painting. I always feel like I'm making sculpture. I hate using canvas," said Semercioğlu, sipping a coffee at Pi Artworks under Istanbul's summer sun. "You can feel my wire paintings. The light and forms are different when you move. It's real material, perspective, depth. You can say it is op-art, also kinetic art, I sometimes say."

At her last solo show in 2015, "Woman on the Wire" in London, where Pi Artworks is headquartered, Semercioğlu catapulted her figurative and geometric interpretations of the primordial matriarch into social import, addressing honor killings and birth control, all the more moving when expressed through the painstaking discipline of knitting with sharp metal wire, vivid as earth and flesh. Desire to Survive repositions her methods, but not her madness.