© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

A smorgasbord of kinetic, sonic and purely visual multimedia works by Pablo Davila have come to Istanbul for his first solo show in the country, titled, "Under one lamp by day, and billions by night."

Its 14 interpretations on the theme encompass a retrospective breadth of past exhibitions at The Pill, towards a kind of morphic resonance in the vein of art. They are housed under the old Golden Horn roof of its highly pliable white cube until July 13.

Inside beneath a colorless square of ivory-hued signage, over the busy exhaust of Balat's main shorefront thoroughfare, Ayvansaray Avenue, a heavy industrial door leads into a fertile audiovisual field. The air hums with an intensive exercise in the development of a counterintuitive ear for repetition and its other. A custom coded Yamaha disclavier piano reenacts the ghostly effects of the player piano, as its keys clamp down untouched.

"Phase Paintings" (2019) by Pablo Davila, perforated canvas, 130 x 100 cm.

The performative installation of music without a musician is a strong metaphor for the ideological divides that rage in contemporary art, where the distinction of visual art from all art is blurred into a fog of minced cerebral debris, and the intellectualism of text and its reference to art objects merges into an inverted logocentrism in which the visible is secondary to its resulting conference of verbalisms. But in Davila, there is redemption. And still, he is not shy to engage the mythic power of naming through an autopoiesis of creation, instilling vibrations that course through emptiness like the tempting serpent of Eden. Its skin, once shed, becomes a trace of its past self. Or, as William Gibson wrote, "Time moves in one direction, memory in another." The quote is part of the literary ephemera that accompanies the show.

"Under one lamp by day, and billions by night" is a surefire psychological thriller of enduring and enlightening discoveries, a feast of sensual inspirations slowly exhaled like a long silence after the frazzled bang of a complex, dissonant chord, meticulously programmed into a midi system for 88 keys. As part of his research, Davila crunched numbers to better understand the pedagogical instrument's potential for harmonic variety.

He came to a common conclusion that is no less stunning for its having been fathomed numerously prior to his personal deep dive into the figures. The number of notational possibilities for pianists to play are two to the 88th power or written out entirely: 309, 485, 009, 821, 345, 068, 724, 781, 056. It is no wonder the keyboard has seduced and confounded the greatest minds in human history.

A stranger in a familiar land

In the hands of Davila, expanded consciousness of the universe is also intimate, personal, flesh and blood. "Nothing Twice" (1997) by the Nobel Prize-winning Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska rests on the piano's mantle where the musician would read sheet music. Its philosophy was summed up by American poet Gregory Corso following Heraclitus's adage: "You cannot step into the same river twice," with, "You can't step in the same river once".

Or, as Szymborska began her poem: "Nothing twice has ever happened or will happen. / That is why we are born amateurs / And will die the same." To accent the unrepeatability of nature in its continuous procession is the forte of Davila, whose Turkish debut is centered by a light bulb swinging at the end of a cable. It revolves silently, entrancing to allure as it deflects. Under the influence of a whirlpool intoxication, the light orbits with the cursed magic of gravity.

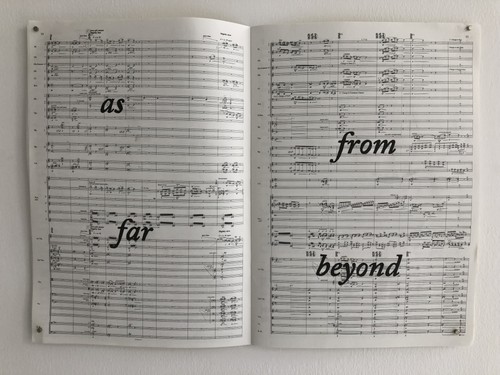

"From me flows what you call time" (2019) by Pablo Davila, music score sheet of Toru Takemitsu's "from me flows what you call time" and charcoal.

Mixed like an erratic chorus of unseeable colors vibrating through the void, the piano resounds, unavoidably present, with a chaos of mechanical precision. It makes for an aural tapestry similar in style to what maddening opacity has ensued in modern composition based on the techniques of 12-tone serial music. Davila further appreciates the image-language of written music made with charcoal and a copy of the score, "From me flows what you call time" (2019).

In between lines for harp, trumpet and violins, the artist spelled out, "as far," "from beyond," injecting a layered, mental texture to the act of reading, from music, to sound to visualization. His work is a vessel, in the guise of a found object (which is both a musical and art term), through which to reflect on the meaning of cosmogony, namely the origins of the universe in every bit of its diverse manifestation. All parts contain the whole, as the whole its parts.

The sound of the first image

The dust of history is apparent at The Pill during the exhibition, "Under one lamp by day, and billions by night." Sourcing the original residue from previous shows, the house curation of Davila's Turkey premier is a dialogue on the invisibility of the past. Some 11 of 14 the works listed as the art on display are in fact not on display. The rectangular frames of artworks by Mireille Blanc, Leyla Gediz, Apolonia Sokol, and Eva Nielsen are subtle against the white walls of the gallery.

There is a circle within a circle among the impalpable art objects lost to time, titled, "Let us go then" (2019), comprised of violin bows. The installation is something of a representation of the practice of orchestral tuning before a symphonic concert, recalling the uncanny cacophony of polyphonous arrhythmic disharmony. As the linear form of the bow creates a circular perimeter against the whitewashed wall, the arrangement evokes a three-dimensional planetary shape.

Over the spherical, round, and waving contours of nature, straight lines are an affront, reminiscent of the impositions of anthropocentric historiography, from national borders to calendar time. Davila has extracted the violin bow from its element in orchestra pits and bluegrass jams among its countless roles that welcome its range from classical grandeur to everyman's row.

Arguably the most traditional pieces of Davila's decidedly avant-garde work are a series of perforated canvases known as "Phase Paintings" (2019). With his most recent work, Davila is advancing his peculiar post-materialist and trans-media approaches to the discipline of contemporary art as a demonstration of being in the present, of embodying timelessness by inhabiting objects, processes, expressions, and placements.

With a kindred spirit to the music of Steve Reich, specifically his "Phase" music, for piano and violin, exacting perforations in his three canvas create the optical illusion of a focus softening and sharpening. One makes the impression of water droplets misting into a cascade of indiscernible, minute detail. Another deepens at its core into a spiral, swept in a haze of constellated points of blackness.

The third of Davila's perforated canvases conveys the visceral sense of charging through the intergalactic starry firmament at warp speed. It is an apt picture by which to consider the rise of a Mexican artist to a unique global stature, as Davila has enjoyed exhibitions across Mexico, the U.S., and Lebanon. In Turkey, his is an auspicious new arrival in the free market of ideas.