© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Minerva, the Roman equivalent of Athena, is the virgin goddess of poetry, medicine, wisdom and strategic warfare, though it is said that she was more a patron of the arts to the Romans than the top-down warmonger of the Athenians. Her smiling marble bust looks up above a polished mantle upheld by the Rod of Asclepius, as to protect and heal entrants into the historic Minerva Han in Karaköy, tempting passersby to admire the antique elegance of Levantine Istanbul.

The divine qualities of Minerva are a welcome metaphor for the building as it temporarily houses the works of three international artists: Ferhat Özgür of Turkey, Knutte Wester of Sweden, and Dejan Kaludjerovic of Serbia and Austria. Into the subterranean floor beneath a spacious reception hall, a staircase leads under the French for "strong safe." It is a vintage vault straight out of early 20th century international finance culture along the Avenue of Banks. Inside, a sequence of three, decreasingly lit exhibits opens with an installation by Özgür.

A construction scaffold is draped with a canvas showing a series of photos. Özgür traveled to the eastern Anatolian province of Diyarbakır to cast a candid light on the conditions in which children play. The centerpiece obstructs the way to the next hall, delaying short attention spans from moving on before contemplating the array of readymade symbolism.

Student and his master's art

M. Kıvanç Gökmen, a young independent curator and artist, recently worked at The Pill as the associate director at its quirky location in Balat, uniquely bringing Francophone artists like Apolonia Sokol and Raphael Barontini to Istanbul, where German and English art worlds have more visibility. Gökmen met Özgür as his professor of contemporary art issues and art criticism at Yeditepe University before the two became fast friends and now collaborators. A year ago, Gökmen transferred to Düzce University where Özgür is currently teaching as a professor in the painting department. Özgür wears the hat of a mentor with a cool demeanor as he navigates the rapid currents of emerging names and movements in Turkey's cultural milieu in dialogue with the global art world.

One day at class in Düzce, Özgür lectured on the video animations, drawings and sculptures of Knutte Wester and Dejan Kaludjerovic, the former with whom he was in a group together show in Göteborg Konsthall and the latter who he knew personally after participating with him in an artist residency in North Ossetia, an autonomous republic of Russia in the Caucasus. In his seat and inspired, Gökmen began to strategize, thinking as a curator. Little did Özgür know that he was sowing the seeds for a future exhibition, the current, "Another Day, Another Life," in which he would show his brand new work, "Nowhere Land," alongside a multimedia presentation by Wester, all under the designs of Gökmen. In the span of three years, his teachings bore fruit.

"According to the given concept, I tried to convert the space into something depressive, where there's no way out. Indirectly, all of the objects here have symbolic meaning, but not directly," said Özgür, as his voice echoed in the underground chamber beside his multivalent installation. He stood between walls that would imaginably tell more tales than he if they could talk. They are now continuously revitalized by the efforts of Sabancı University, which founded Kasa Gallery in 1999.

North by southeast

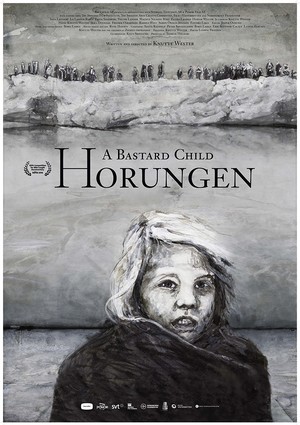

A story is unfolding a few steps inward, to the second hall. Its narrative, and voices are akin to the significance behind the celluloid snippets and artificial structures assembled by Özgür, only it penetrates to the heart of the matter more immediately, like a cold knife. Wester is a multidisciplinary new media artist who employs his handcrafted skill as a draughtsman for the 21st century. Inspired by his grandmother's childhood, he made a 58-minute animation documentary titled, "A Bastard Child" (2016).

"A Bastard Child" (2016) is a documentary animation by Knutte Wester (photo courtesy of www.taskovskifilms.com).

In the minds of Turkish nationals, Sweden seems an idyllic place on the map of humanitarian achievement worldwide, with its economic egalitarianism, charitable outreach and liberal immigration. Wester unravels its more complex origins. His grandmother, born in 1909 out of wedlock in Sweden, knew the harsh realities of orphanages and prejudice that made single mothers into prostitutes and delegitimized the existence of fatherless children. At one point in the heart-wrenching, utterly beautiful film, the strong, wounded mother takes her daughter by the hand and decides to drown herself with her child, but she cannot break the midwinter ice.

"A Bastard Child" questions the notion of legitimacy in the European tradition of thought and culture that was established by racist and sexist orders based on inheritance and nationality. Within the round of current events, the film is insightful as a comment on migration issues in Europe, as they ensue unabated with the wholesale effect of reinforcing and abolishing both right and left definitions of nationalism. The sense of belonging is crucial to human groups. When children, as newcomers, come into the world into a bounded society and do not fall into socially contracted and determinable identities, they threaten the status quo. In response, extreme conservatives might target anyone, including honest-to-goodness freethinkers.

The last room is completely dark. A projection flickers. Its ticking recalls another age, decades ago, before the ruthless atrocities of the 20th century had spilled into the present. "Another Day, Another Life" sinks into the eeriest depths of the prepubescent subconscious with the photographic installation, "The First of May, 1977" by Dejan Kaludjerovic. It forwards a deep sense of foreboding before the genocidal breakup of Yugoslavia, pictured in the microcosm of a violent incident during a playdate. A deadpan voice-over recounts the tale: "She remembers the boy and the girl teasing each other and fighting."

"For my first exhibition as an independent curator, I wanted to start with childhood. First, it is something easy. But, on the other hand, it is something really hard and dangerous. I really wanted to avoid agitating with this exhibition. I didn't want to try to show how children feel, or how they suffer. I wanted to ask to myself first: What am I doing with art?" said Gökmen, standing next to Özgür at Kasa Gallery, emphasizing that he could never have done the show without him. "At some point, art represents a way of communication. Or is it a catharsis?"