© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Outside on the street, the tramway runs along the wide, pedestrian Istiklal Avenue, bustling with the sale of treats and trinkets. Hawkers shout in Arabic, luring youngsters with globetrotting families in tow for an ice cream cone, irresistible even in the dead of winter, especially when playfully purveyed by smiling men in embroidered vests and fezzes, clothing styles a century outdated. As soft snowflakes fall in slow-motion under the Thracian sunlight, cold rays bounce off the neoclassical facades of bygone Greek residences and European establishments, glorified by semi-indoor hallways named after historic Ottoman territories and adapted from the ancient architectural form of the stoa, with its gilded marble since renovated to a luster.

The proudest commercial drag in the city where East and West meet appears eternally peopled to the brim, all the more so in recent years as waves of Arab-speaking migrants, including some half a million Syrian refugees, have called Istanbul home, often before confronting harsh realities behind the promises of universal humanity and economic stability in northwestern Europe. The multi-center business complex inside the Mısır Apartment stands ornate on the relatively calmer passage along İstiklal - which, in Turkish, means independence - between the 15th century Galatasaray High School and the medieval Genoese port of Galata.

The building's exotic title, "Mısır," is from the Turkish word for Egypt and the Arabic for garrison, denoting occupation in the land of the Pharaohs by settlers from the Arabian peninsula.There are two separate rooms on the second and third floors inside the converted apartment building where Zilberman Gallery houses relatively modest gallery spaces to exhibit contemporary art. It is a charming, fashionable cultural institution in Istanbul's core, which under the direction of founder Moiz Zilberman for 10 years and running now also encompasses a sister annex in Berlin. The art on view in its chambers has that characteristic, moody indoor lighting that both sterilizes and transforms the still air into a place meant to plumb the depths of creative inquiry, led by minds perpetually tasked to shift the paradigms of individual identity, intellectual work, and innovative creation, manifesting new concepts of being and perception for footsore audiences prepped for change in an increasingly internationalized world of boundaries that fluctuate between obstructive fixation and total dissolution.

In general, it is the case that the specialized worlds of contemporary art, particularly the realm of indoor, neighborhood gallery exhibitions, are one of the last frontiers of unabashedly public, process-based work, mostly conceived by educated specialists and lifelong practitioners of certain hands-on methods to investigate the nature and efficacy of communicable, independent productivity in the interest of cultivating provocative, opposition-informed thought. These interpersonal values and modes of civil society are paramount in a capitalist-driven, nationalist-ordered world, where popular growth is defined by the consumption of ready-made artifacts manufactured by a decreasingly human, cultural engineering.

A globe of misfits

Exile begins like an abstraction, its roots supplanted, by definition, into a conceptual reality defined by loss, towards an ideal, levitating as it were, sustained by involuntarily unsettlement. Antonio Cosentino, whose signature, flat-stemmed cactus marks his "Untitled" (2017) charcoal on paper, alludes to a common motif in, "An Exile On Earth," with his focus on a loaded vehicle. A ghoulish cartoon of a skeletal, human figure reaches out from the trunk, encumbered by the cluttering cargo. With his subtle, crafty touch, Cosentino drew an ambiguous type of automobile. It is not clear where the front is, or the back, or if it is even oriented to a grounded, binary sense of geographical direction. Beside the simple sketch, his mixed media, "Map" (2017) outlines a fictitious wall constructed west of the archaic city of Constantine, placing the current, geopolitical moment as comparable to a level of development that was common in antiquity.

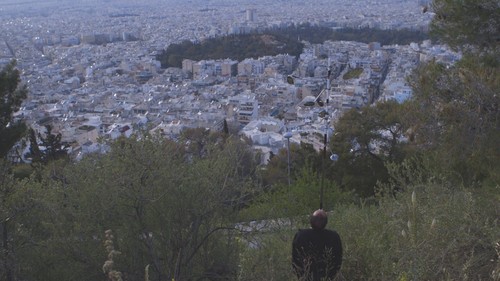

A still from "Pre-Image (Blind As The Mother Tongue)" (2017) by Hiwa K.

The series that follows is by Zeynep Kayan, also a Turkish artist whose works seem to comment indirectly, more theoretically, on themes that become life or death for the compatriots of the artists whose works are curated at the heart of the exhibition. Halbouni, for example, created in solidarity with the plight of his fellow war-torn Syrian nationals with his "Nowhere is Home" (2015-2017) and "Monument" (2017) series. And ultimately, Hiwa K returns to the endangering migration path and extinguished urban memories of his Kurdish Iraqi origin story with his gripping pair of videos, "Pre-Image (Blind As The Mother Tongue)" (2017), and "A View from Above" (2017). In a cleverly framed sequence of 18 stills from her series, "Studies for staying in the middle, or changing quickly from one state to another" (2018), Kayan visualizes the existence of physical dividers as a system of opposites open to wholesale reinterpretation.

A barrier that would block a person from view, and from movement, is not an absolute, Kayan might argue, but one of many proofs suggesting the innate malleability of material and the ability to sense and reinforce, or redefine, its reality. Her video, titled after the same series as her photographic work, animates her convictions in the way of a performance. The face of a lone person is unseen, unframed. The body demonstrates, on behalf of all, the contours of human enclosure, it being a function of perspective. The gallery then broadens into a spacious succession of invitations into the makings of multimedia objects and acts of installation based on the primacy of the ideas that conceived them. While created for distinction, the artworks are not in the least divorced from worldly concern. They might even prompt its redirection.

The first edition, fine art prints of snapshots from the "Monument" series by Halbouni are as glaring as they are imaginative, refreshing as they are avant-garde. Any device to encapsulate his effect is doomed to disappoint, as words fail to convey the presence of coach buses turned upright before the architectural splendors of the Maxim Gorki Theater and Kunsthaus Dresden in Germany. The installation and its impressions as prints give literal, material weight to the many overarching speculations that have emerged following the EU migrant crisis. With its front end pointing to the heavens, the buses might symbolize the idyllic stargazing of migrant dreams, to ascend north, become mobile, economically, to stand tall as human beings, strong, visible.

Where automotive technology is seen as a source of German national pride, to baldly display bus mechanics in the context of migration in iconic public spaces in Germany is to stress that by bringing such technology to the greater world, it is no wonder if people abroad use it to how they will, seeking to wield such power at its source. "Monument" could be seen as a metaphor for the outstanding, repercussions of European colonization and the latest generations of post-imperialist hegemony that continue to strain Western Europe, as former subjects of its empires, and equally victims of its foreign conflicts, reiterate the timeworn saying: all roads lead to Rome, now to Berlin, Paris, or London.

The wandering everyone

The emotional pulse of "An Exile On Earth" is narrated by Hiwa K, whose videos are deeply moving. "Pre-Image (Blind As The Mother Tongue)" is written with powerful originality and personable frankness in a voice-over monologue. "Feet are never based," says K, emphasizing the fundamental necessity of movement as essential to the human experience. The artist balances a pole stretching upward with an eccentric web of mirrors, as he walks through nameless terrain overland from Mesopotamia, through Turkey, to Kavala, in northeastern Greece, and down through Athens and the tent cities of Piraeus, into a vague rendering of Italy, observed askew as from the weary, survivalist eyes of a migrant come from the far-flung, embattled reaches of the Middle East, as K had from Iraq's Kurdish region.

"Pre-Image is indeed a central piece for me, I even wanted the artist's voice / sound / narration to be diffused in the entire space to invite / call the audience, and accompany the audience, throughout the exhibition space," wrote Çelenk Bafra, who enjoyed the challenge of working within the Zilberman Gallery space in Istanbul as her smallest curation yet, since she mostly collaborates with museums and biennials. "I don't think the exhibition is about the migration crisis. It's rather about being an artist and living as an artist in a world with constant mobility and migration."