© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

In his last days, Tosun Bayrak sat with his people in the evening hours, as night fell after the ritual zikr ceremony finished, the dinner tables cleared, teas served and all ears readied to listen to his soft, elderly voice speak in between regular puffs of Samsun cigarettes as he led the traditional group discussion known in Turkish as the sohbet, in which perennial wisdom is relayed by word of mouth from master to student on the Sufi path, unbroken since time immemorial. From the Arabic word for remembrance, the zikr is a pronounced, collective dedication to the rhythms and harmonies that issue from the vowels of sacred names in Islam. Its multiple forms of prayer recollect a higher union with the omnipresent religious experience of transcendent, communal absorption through movement and music.

To his closest devotees, he was known lovingly as Tosun Baba, spiritual father to the dervishes who he guided beyond selfish egotism. More formally, in the wider circles of his organized faith, he was Shaykh Tosun al-Jerrahi. It is a title extending from Hazreti Pîr Muhammad Nureddin al-Jerrahi, who lived in the 17th century and founded a Sufi order that remains active by his tomb in Istanbul's old city district of Karagümrük. In the summer of 2017, as seasonal rains swept in from the Atlantic archipelago of New York City to wash the forested border of New Jersey, he emerged from the verdant ecology beneath the sleepy minaret of his emerald-lit American mosque in a place called Chestnut Ridge. It was where he continued his greatest life's work to the very end. Months before his death, none could be sure that he would appear on such nights, as he was said to be in ailing health. When he did, the reverent ambiance could be felt in the air with every breath.

He whispered to a bold, young woman who had traveled from Turkey to kneel beside him. She was with an American man, her partner. Before beginning the sohbet, Tosun Baba first asked if he would convert to Islam then and there to be with her. In front of an open-hearted crowd of onlookers, he did, and took his place among the believers. The sitting room was lined with countless books encompassing a kaleidoscopic range of interests that mirrored Bayrak's intellectual history, spanning studies from Buddhism to architecture, Gurdjieff to Rumi. Its richly-lined shelves wound throughout the lushly furnished interior of the lodge, displaying his translations of early medieval Muslim mystics Ibn Arabi and Abd Al-Qadir Al-Jilani, next to his 2014 autobiography, Memoirs of a Moth, the only book of original prose that he authored. Written in a spare, third-person narrative style, his life chronicle serves as an ample reflection on the role of the Turkish nation since the dawn of the republican era to preserve and advance its shared cultural heritage with the world.

A few early brushes with fate

It was December of 1968 and Tosun Bayrak had not been back to Istanbul, his native land, in 17 years. He was then in the company of his second wife, Jean, who would remain by his side till his passing. Later, during the sohbet in New York in the winter of his life, she smiled back at him as he complimented her beauty with a twinkle in his eye, even at 92, sharing a moment encircled by the warmth of congregants, where she sat humbly inconspicuous among his many followers. They exhaled visibly in the frigid train station of Haydarpaşa awaiting passage to Konya, to witness the Sema ceremony performed by authentic, whirling Mevlevi dervishes, who, in the spirit of Rumi, symbolically enact the mystical wedding of all humanity with spiritual perfection, one soul at a time.

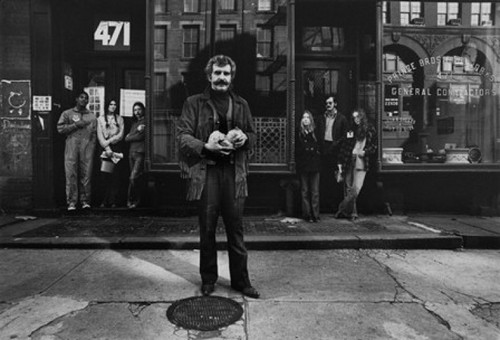

Tosun Bayrak in New York, 1971, when he invented Shock Art (photo courtesy of Milli Reasurans Sanat Galerisi on the event of his 2016 exhibition in Istanbul).

The ceremony was underwhelming, as even then, audiences had come from afar attracted by its mere romantic exoticism, only to distract those genuinely interested in realizing a way in to the Sufi path. By then, Bayrak and his wife were not committed to a spiritual discipline. In fact, he was raised without religion, but since high school, and especially as a student and artist in the US, he read Hindu and Buddhist philosophy, and for years attended meetings at the Gurdjieff Center in New York, pursuing the 20th century Armenian-born thinker who forbid talk of religious dogmas in favor of experiential consciousness. His first encounter with Islam as a living practice occurred when he stayed with his eldest aunt Fatima on weekends as a boarding student at Robert College. In her shadow, he watched her pray five times a day, and fast during Ramadan, a stark contrast to his mother and father who only rarely led him inside a mosque.

Bayrak found art before religion. On the tenth anniversary of the Turkish republic, in 1933, he was seven years old in the company of his grandfather, a dyed-in-the-wool Ottoman clerk and lover of rakı named Ihsan Efendi who encouraged the little, fledgling artist in his family to grow by taking him to Topkapi Palace and the Greco Roman Antiquity Museum where he could best learn to draw the human figure. In his last year at Robert College, he became enamored with the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore, and the Bhagavad Gita, intrigued by its eastern mysticism like any curious man with a secular, western upbringing.

He soon aspired to become a poet, or an artist.

Before boarding a decommissioned American troopship in 1945 bound for the University of California to study architecture, his father gifted him Rumi's classic poem, the Masnevi, and he began a long friendship with the painter Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu at his workshop in Istanbul. He later met Eyüboğlu and Abidin Dino, another great Turkish artist in Paris, where he studied under Andre Lhote and Fernand Leger. His cultivation in post-Impressionist French painting soon turned into his affinity for the Abstract Expressionism that developed in America as European art disembarked in the New World during the 1940s. In the meantime, Bayrak enjoyed an eccentric bout of the artist's life outside of London with a quartet of outlandish Turkish mates while studying art history, despite skipping many classes, at the prestigious Courtauld Institute.

Among his compatriots were the poets Bulent Ecevit, who became Prime Minister of Turkey four times, and Can Yücel, a legend of modern Turkish verse. Interestingly, at the time, Bayrak had already published a book of poems, titled, And, to favorable reviews, and would release yet another, To Speak Without Speaking, while living in Ankara, where he found the wherewithal to produce the first Turkish translation of the United States Constitution. Back in England, he knew Ecevit and Yücel were better poets, but they were unknown. He stamped around proud of himself until Yücel's father, Hasan Ali Bey came to visit and critiqued his loose way of life, which they coined, Bourgeois Mysticism. In the same breath, Hasan Ali Bey introduced Bayrak to Sufism, as a philosophy of human perfection already complete and proven.

"The Americanization of Tosun Bayrak" (1965), by Tosun Bayrak, an artwork posted by one of his ardent collectors, Istanbul Modern, when Bayrak passed away.

From outsider artist to Sufi master

On that fateful train ride to Konya in the winter of 1968, a lady named Munevver Ayasli heard Bayrak and his wife speaking and thought they were both foreigners. Bayrak had arrived only recently to his native country after being away nearly two decades, and when he first saw one of his little cousins, his modern Turkish baffled him, as he had been educated in the Ottoman language. Munevver introduced herself and her travel companions, who were the mother and wife of a direct descendant of Saint Mevlana, a Celebi. It was an auspicious meeting as it would eventually lead to his discipleship under Muzaffer Ozak Efendi, who brought the Jerrahi order to America. But even after conversing for almost the whole ride through the Anatolian heartland about Sufism, and the sheiks and dervishes of Turkey who had persevered despite Ataturk's secularization reforms, Bayrak lost her address after she had given it to him with an invitation to see her back in Istanbul. Bayrak returned to the US after his yearlong sabbatical from his hard-earned professorship at Fairleigh Dickinson University where he established its Fine Arts Division literally from the ground up. The year back in Turkey had involved a number of life changes, including the death of his father, Hasan Tursun Efendi, to whom Memoirs of a Moth is dedicated with an inscription that explains how, while he did not teach formal religion, he conveyed the most fundamental principle in Islam called, adab, or manners, the essence of kindness, tolerance, patience, gratitude, unity, loyalty, truthfulness, and sincerity above all. Despite receiving the enviable Guggenheim Award in 1965, and inventing Shock Art in downtown New York, among many other claims to historic prominence, Bayrak lived many and various lives. He transformed when most would have conformed. His memoir has three sections, Know, Find and Be. It is the honest testament of a wise, gracious soul who raised the spirit of humanity from profound depths, through expansive breadths, to new heights, by acts of fellowship, to embrace true oneness.

The cause of unity became a prime mover for Bayrak as the sheikh of the first Jerrahi mosque in America, which he opened in Chestnut Ridge in 1990. Its growing community immediately helped genocide victims during the breakup of Yugoslavia, especially Bosnian students who Bayrak assisted during his trips to Zagreb. In 1994, he met Fetullah Gülen, who offered him support when Robert College and many private schools would not, and wrote of him endearingly. Unfortunately, Bayrak could not see the truth about the cult before the failed coup attempt by FETÖ. Memoirs of a Moth was published in 2014, well before the failed coup attempt by Gülen's FETÖ on July 15, 2016. When Bayrak appeared in Istanbul for his winter 2016 exhibition, "Fasa Fiso" at Millî Reasürans Art Gallery, he condemned Gülen in an artistic statement depicting the dollar as an evil that FETÖ had exploited. At age 90, he was still an avant-garde globetrotter and radical humanist committed to freedom, peace and creativity.