© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

A fashionable and confident woman walks in with a powerful stride, a bolt upright back and disarming poise through the sweeping, heavy doorway of the stylish, neighborhood gallery Pg Art, clicking her heels on the rough, pearly floor against walls that gleam in a baby blue so immaculate it's nearly transparent, its pale shade as devoid of shadow as the clearest of summer skies on those bright days when warm air is shot through with rays of heavenly fire purified by the emptiness of space beyond the earthly horizon.

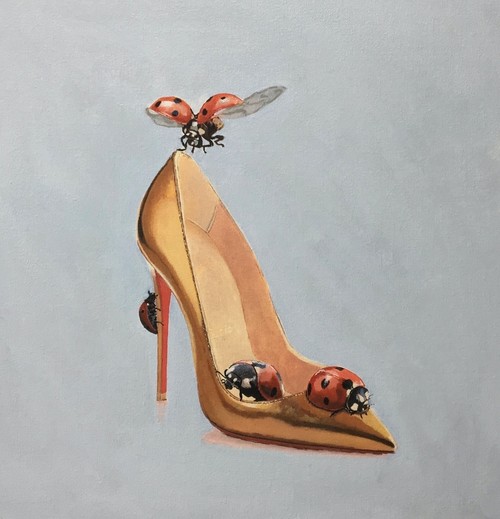

She takes off one of her heels and lays it to rest on the tiles that reflect the flawless azure, where only the slightest, amorphous patches of spectral variation appear to the onlookers, who are unwavering as they stare at the irresistible, superlative bounty of female self-expression. They watch as she fades into the entrancing luster of the luminous, monochromatic background that is at once unpolished, left raw like the cloudless fortuity of an atmosphere unobscured by even a single tuft of moisture, and yet is entirely, deeply crafted. Eyes drift to the heel, golden through and through, a profound, substantial metallic blonde refined from the heart of the earth, and run with a sole strip of candy red up its dagger-thin stiletto.

The acrylic paintings of Elsa Ers express the beauty of female presence and its loss with stylish empowerment.

They keep ogling her lost heel. In time, a buzzing of insect wings is heard approaching through the cerulean ether. A quartet of ladybugs land on her abandoned shoe. One climbs up the stiletto. Another lands, wings outspread, on the heel, as the other two, somehow larger yet still dainty, explore the point. The ladybugs are transfixed to the object whose aesthetic and purpose is kindred to the name they assume with natural authenticity. Elsa Ers stood the longest to capture the moment as it graced the collective subconscious, when she fished it out of the reaches of the imagination to arrange the feminine insect with a likely, though an artificial friend from the human kingdom, a high heel. It is one of 13 paintings that decorate the walls at Pg Art Gallery for her second solo show, "In Absentia," to evoke a very human death of nature.

Dining with the mother artist

A white-tied waiter pulls back the woman's chair with a soft grin. He notices that she has lost one shoe but does not comment. "She must know," he thinks. And as she crosses the leg of her barefoot to her left, the waiter then notices her glistening pedicure, with toenail polish so fresh that it reflects the restaurant's natural light like a silver spoon, even as a grand mirror. Tablecloths are colored a milky blue and textured with a tickling, effervescent grain. Her fork is to the left, knife to the right, and her spoon is placed horizontally over the plate, a black and white weave of designs balanced delicately to open a space in the middle, where a large, multicolored beetle is served, paired with a couple of ladybugs. She cracks her toes by a tight clench of her foot and digs in with a broad smile.

Ers is looking at her from above. She paints the dish with a meticulous sense of detail and riveting color, though it is like an abstract object flung through outer space, motionless as it casts a shadow over the pale blue background. The woman, nowhere to be seen, asks for another fork. Its metalwork is more intricate than the one given to her on arrival, impressively engraved as delicately as wood with the f-holes of a classical violin. She raises the filigree handle by pressing her pointer finger against her thumb to pierce the beetle after dousing it in pink cream and a halved strawberry. The lights go out around her and all is pitch dark except for the glimmering rainbow exoskeleton of the beetle and the gilded utensil fit for royalty.

The colors of Elsa Ers are vibrant thanks to her choice of acrylics, as she paints fish, insects and snakes into a neorealist commentary on greed, consumerism and selfishness.

She has really come for dessert. Her greed is shared by the world, as she sits alone wishing that she could eat and buy everything. She looks across the restaurant toward the entrance and espies a dragon-like fish immersed in blue light, attracted to a glass marble in which the colors of its electric indigo body and florid ginger tail are reflected. "It is Narcissus," she tells herself, imagining the mythical personification of selfishness, long submerged in the waters of its visual echo where it has ever spent lifetimes looking at itself. "I am in beautiful company," she thinks.

So, she orders a cake. The first slice comes flying with four lively monarch butterflies delighting on the ruffles of frosting. Her total field of vision behind the thick slice and over the vegetal-designed china plate transforms into a camouflage design, of coral, aquamarine and beige colorations. Two small fish float through the air and steal a knowing, almost judgmental glance at her. She is uncomfortable with the whole situation and orders another slice, something different. It soon arrives on an identical plate, a shallow bowl crested with gold at the lip and painted with thin, green leaves. The butterflies have flown away, and to replace them, a hybrid creature in the form of a hummingbird and mosquito swoops down to taste the frosting. And a new fish also swims over, now gawking at her wide-eyed, innocent and half-frightened. The cake is made of raw meat. Despite the background giving way to a simple tint of spacious, pearly gray, she is uncomfortable and does not even look at her fork, never mind take a bite.

To be human and female

She returns home before late, looks in the mirror, and readies herself to sleep. Her dream is unsettling. The walls of her bedroom dim to total darkness. She hears a voice say, "You are what you eat." It is on repeat, like a chant, only somehow played from a shot, vintage turntable. And then, a la Kafka, she feels her legs as the sharp, awkward limbs of a bug. Her eyes are kaleidoscopic, opening to the world through a honeycomb of lenses. It is dizzying, and more, the ground beneath her writhes with a slimy, reflective sheen. A massive constrictor slithers under her every crawling step and then she looks up, and the world is glowing. A school of phosphorescent jellyfish wanders in a spontaneous mass. She is lucid and seeks a way up from the lightless ocean floor.

Ers painted the snake as it rose from the watery depths to twist around the stalk of a purple flower only to peer out above the canopy of petals to spy a fish of similar hue, of the Tyrian variety long attained from mollusks and worn by the ancient rulers of Byzantium. The spotted, leathery scales of her serpents are photo-real, deceiving the eye, touched with shade and coiled around the olive-green stem. There is a feeling of mystic ascension to her works, especially the circular disks where human forearms appear out of opaque paint lathered liberally, though with careful attention to the smoothness of her colored continuity. The beetle, fish and butterfly emerge into a vision from sacred orbs, raised and offered to the spirit of the muse.

And others woke from the nightmare born in 1915 to the public imagination from Prague, the "metamorphosis" that changed novels, writing and thinking. She listens to Kafka outstretched over a floral wallpaper backdrop, adorned with a stork origami accessory, traversing the abstract space that leads into an emerald forest of domestic perennials and sugar-coated, candied fruit. She takes on yet a new form, as a viridescent, jeweled beetle walking lightly over a pile of rainbow gummy worms. "Painting in this instance is more a way for me to sort my feelings and create a commentary. There's definitely something instinctual about the way I work," Ers wrote via personal correspondence, as she looks for meaning and concept in her artwork after completion for a more objective take, recently switching to non-toxic acrylic while working from home with her daughter close by, leading to her exploration of more vibrant colors." It's going to sound extremely plain and simple, but more so than anything else, motherhood has taken away my time and my patience. Not having enough time — though it seems contradictory — was a positive influence. Suddenly I didn't have enough time to wonder, ponder, have bouts of crippling self-doubt, all of which are common in the process of making art."

"'In Absentia' was more a personal evaluation of my own struggles with motherhood than a feminist statement. But a large part of that struggle is due to being a woman in the Middle East. Up until I moved to Tel Aviv, I lived in metropoles, specifically ones that don't have enough room for nature. Istanbul has long been fighting a losing battle to preserve its greenery. Israel, in that aspect, was a complete novelty for me," wrote Ers, a Turkish-Jewish painter who sees Palestinians are the best artists in the region. "I'm a complete city girl at heart, but I tend to escape to nature when things get too hectic in my head and I need a break. I'm fascinated by animals, especially by exotic insects as of late. My work is influenced by my upbringing and past in Istanbul than my current life in Tel Aviv. I'm still figuring it all out, and that exploration process ends up as paintings."