© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

The exhibition, "Poetry of Stones, Ani: An Architectural Treasure on Cultural Crossroads" opened at Depo, Istanbul on March 14. The exhibition is dedicated to the restoration work that has been done on the site, starting from the Russian archaeologists to today's collaboration of Turkish architects and Armenian stonemasons. There are, naturally, photographs, quite big ones too, and a stroll in the two stories of the Depo building in Karaköy gives one a sense of having glimpsed the grandeur that is Ani. The exhibition, of course, remains a "lifeless imagination" as Turks like to call the medium of the photograph, but an imagination nonetheless that will make every single visitor book a trip to Kars.

As part of the exhibition, Depo also held a panel about the history of the restoration work in Ani, and the project's current status. Carsten Paluden Müller of the The Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research moderated the conversation between Armen Kazaryan (The Scientific Research Institute of Theory and History of Architecture and Urban Planning), Yavuz Özkaya (Restoration Architect) and Vedat Akçayöz (Researcher-Photographer). It was a revelation to find out how much work goes into just keeping the "ruins" in their already dilapidated state, preventing them from crumbling down altogether. As the Red Queen says to Alice: "Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place."

The restorations and the support work done in Ani, it turns out, started in 1892, after the Russian invasion of Kars. With Empire come the archaeologists, and in this case it was Nicholas Yakovlevich Marr, a Georgian-Scottish orientalist from the University of St. Petersburg. There are several black-and-white photographs of Marr in the exhibition, at work both in the field and in his study. The one in his study is particularly dramatic, with light coming in from the window behind him, obscuring his face, so you are drawn to the larger than life statue of King Gagik I (11th century), with beard, side burns and a huge headgear that makes him look like a Hasidic Jew, his arms thrust forward. Those arms, the caption tells us, are supposed to be holding a miniature model of his church Gagkashen, which, in the photograph stands on a pedestal to the right of Marr. A quick internet search as to the whereabouts of this incredible statue yields the result: "Statue of King Gagik I of the Bagratid dynasty (reigned 989-1020 CE), excavated at Ani in 1906 by Nicolai Iakovlevich Marr and lost since World War I." The church itself, too, is one of the more devastated of the buildings, there are only parts of walls and ornate column heads that give a glimpse of its former grandeur.

The exhibition is a revelation for those who have not been, and a rediscovery of Ani for those who have failed to prepare well enough before a visit. With or without a guide, Ani is a daunting site. Entering the city through its majestic walls you are overwhelmed by the sheer expanse and resign yourself to missing some of the buildings, unless you are planning to spend a couple of days rather than the half morning that is usually given to Ani trips. I was stunned by a photograph of the Baron Palace for instance, with its Seljuk geometric wall patterns, a contrast to the frescoes and carvings that seem to dominate the more easily accessible buildings that are on the central route of the site. The Baron Palace, the caption tells us, is the only secular structure standing in Ani, and one that bears witness to the various architectural influences the city was under through its history. After seeing the photograph, I did a double take and went back to the large aerial map locating the several ruins to see that Baron Palace is tucked away at the foot of the walls to the very right as you enter the city. Noted for the next visit.

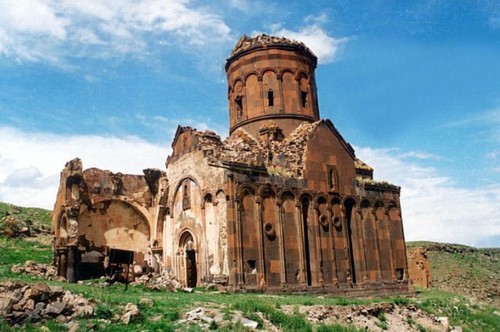

The symbol of Ani remains, however, Surp Prikch, Church of the Holy Redeemer, looking like it is waiting for its lost half to come back. Much of the panel discussion was taken up by Surp Prkich, as it was one of the main concerns of Marr too when he came to do work in Ani. The experts now working on the building, represented on the panel by Yavuz Özkaya, have discovered that Marr's 1904-1905 "fortifications" themselves are now weak. There are graphs and sketches in the exhibition showing layers of work by Marr and the current restorers. Özkaya also told the story of how some of the much-needed columns on the façade were made from stones from Armenia, worked on by an Armenian stonemason.

Another revelation about Ani comes from the local researcher Vedat Akçayöz, who has been discovering an "underground city" beneath Ani, which seems to be much older than the buildings above ground. His explorations "inside" the slopes that lead to Arpaçay have also revealed several "pigeon houses," with pigeon holes whose numbers must be in the hundreds. The photographs of these incredible structures make you realize the importance of Ani at the crossroads of trade routes, the pigeon holes corresponding, one can say, to the fiber cables that connect modern cities to one another. The underground city is now recognized as part of Ani as a UNESCO site.

Akçayöz emphasized the unfulfilled tourism potential of the site, and members of the audience were quick to voice skeptical views about what huge numbers of tourists would do to a site that is already difficult to sustain in its current state. Having had the privilege of seeing the site myself twice, I am of course with the naysayers, that maybe it is better to keep Ani moderately less-visited than some other sites. Particularly when the tourism infrastructure at the site right now is near to nil, although more and more numbers keep visiting every year. When I first visited in the summer of 2016, there must have been about 10 people on the grounds. When I went again in the January of this year, there were probably about 100 people there.

During his talk Özkaya also spoke about the camaraderie between the Armenian stonemason and the Turkish architects and workers on the field who had learned some Armenian, to speak with this artisan whose work they admired. Özkaya says Arayik Usta has been called the stonemason who will heal the wounds of Ani. It is, Özkaya says, Ani, and not least through this cooperation, that actually will heal our wounds.