© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The contemporary, living Danish painter Per Kirkeby is a household name in his country of origin and increasingly around the world, certainly throughout Europe. In the midst of the cultural paradigm shifts of the 1960s to '70s, immersed in pop art and avant-garde music of the American new wave, he evolved from his training in scientific naturalism to a more abstract take on the surroundings that held his most enduring interests, both personally and in concert with his national heritage. Kirkeby first took part in a disciplinary break from the norm entering the Experimental Art School in Copenhagen in 1962 the year after it opened as the only real alternative to the Royal Academy for serious, life-practicing artists.

After returning from his second expedition to Greenland, his head was filled with the poems of Michaux, the compositions of Cage, the events of Fluxus and so he began to simply improvise his way through the new creative liberation. His contemporaries advanced the fronts of independence from the old lines of patronage that had defined and objectified art into another commodity chain enforced by the royalist, orientalist, naturalist, realist, materialist.

Modernity and Mysticism

Somewhere along the way, arguably while attempting to clear a path through the mystic haze of the Orient (only thickening it all the more), early modern artists began to catch on to the greater creative transformations that changed the identity of representation and its politics. Instead of realizing a viewpoint, a portrait, stilling life to a moment, they made works that expressed inner life, the emotional psyche. The poet William Blake illuminated the essence of the idea, and the novelist Aldous Huxley echoed him to cleanse the doors of perception, to see all as it is: infinite.

As the saga of history culminated with the collective fiction of modernity, artists finally led the way to brave the interior worlds of the soul and intellect within and despite outward appearances to endure the metaphysical tension where unshackled individualism meets the demands of the world. In the light of such historical philosophy, the painting by Per Kirkeby that Tate Modern purchased in 1998, "The Siege of Constantinople" (1995), is especially striking. It is a gargantuan oil on canvas at four plus meters tall, overlapped with cartographic translucence, textured with rough intersections of crimson hues that evoke the flame and blood that doused New Rome on May 29, 1453, into the flood that became Istanbul.

Understandably, with respect to its sheer size, the painting is not currently on display at Tate Modern where space under its world-famous name is at a premium. That said, Kirkeby's artworks, "Stelae" (Laeso IV & V, 1984), are exhibited in the curated series "Between Object and Architecture." Its dialogue with the geometry of the everyday invites subtle, experiential encounters with sculpture on the second level of the Blavatnik Building as steeped in the museum architecture that seamlessly integrates the brittle aesthetics of industrial extinction with the sophistications of its minimalist simplicity. Kirkeby saw the proportions of the human hand in brick and was then visited by the muse while gardening on the Danish isle of Laeso. Its layered mortar is comparable to his abstract painting techniques and further draws from his geological education and builds on the weight of cultural history and its archetypes.

Another Brick in Kirkeby's Wall

To casual eyes roving in the midst "Between Object and Architecture," the art of Kirkeby has the characteristic, intellectual difficulty that is both the cross and signature of what has entered the popular lexicon as "modern art." It is a term generally synonymous with the incomprehensible or absurd to express freedom from social habit and norm. Other works, such as the interactive, Moorish latticework panels and filigree screens by Cristina Iglesias, titled "Pavilion Suspended in a Room" (2005), for example, are more immediately approachable. And yet Kirkeby is not one to so easily brush off as one among the droves of postmodern contemporaries divorced from worldly concern. In 2009, the critic Andrew Graham-Dixon renewed the conversation on his painting "The Siege of Constantinople" in the Sunday Telegraph, pointing to its resemblance to Eugene Delacroix's "Entry of the Crusaders in Constantinople" (1840), set in 1204 when Istanbul shed bloody tears in the face of pre-colonial Western expansionism.

The Guerilla Girls are an all-female collective who remain anonymous by naming themselves after dead women and for a current Tate Modern exhibition speak through texts that visualize inequality in the arts through orientialist visions.

The stratified Byzantine shadows of Istanbul would captivate the imagination of Kirkeby throughout his artistic life, especially in his paintings since the 1980s. In that sense, he has planted his feet squarely among the very core of his chief predecessors in Danish art history. Presently, for example, the National Gallery of Denmark is exhibiting "A Party of Chess Players outside a Turkish Coffeehouse and Barbershop" (1845), the most conspicuous artwork on display of its kind that is based on Turkish history, conceived by the painter Martinus Rorbye who was evidently more aloof from Ottoman territory compared to his utterly impressive, adventuring contemporary Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, who saw her orientalist subjects face to face. Rorbye painted from drawings in Turkey once back in Rome and Denmark.

In his defense, his field sketches in the Ottoman Empire of the 1830s, mainly in Istanbul and Greece, are considered remarkably early examples of such exacting detail. In truth, he followed in the footsteps of his renaissance compatriot Melchior Lorck whose oeuvre as the first significant individual Danish artist in history also created the greatest visual record of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. Today the works of Rorbye are the toast of classical Danish painting as they now grace the most prestigious art galleries in Denmark, from the Aarhus Museum to the Queen's Library. In retrospect, it is clear that he made art for the sticky hands of buyers taken with the unabated commoditization that is the mystique of the East. And the legacy of irretrievable Danish orientalist painting in private collections attests to the fact.

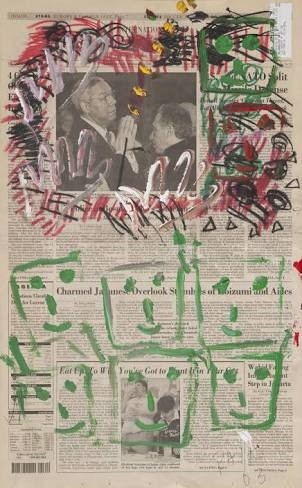

Nam June Paik, the Korean artist praised as the founder of video art, sketched a mixed-media work in 2003 in New York after the International Herald Tribune story on Colin Powell's visit to Ankara.

Tate to the Turks

With blazing self-awareness, Tate Modern curates, for lack of better words, the art of art. According to its vision, artists from virtually everywhere are shown. Yet, on March 18, there were no Turkish names on the placards where artists enjoy global recognition, not overtly. Many works hailed from surrounding regions, though not modern Turkey. In current shows, Jumana Emil Abboud, the Palestinian installation artist, reimagines her folkloric traditions.

Nazgol Ansarinia, the Iranian video artist, explores Tehran. Marwan Rechmaoui, the Lebanese mixed-media sculptor, critiques Beirut. And with a close read into the fine print, Turkey does make a couple of special cameo appearances. It is first plain as day in one work by the late Nam June Paik, "Untitled" (2003) of acrylic paint and pastel on a front-page edition of the International Herald Tribune when Colin Powell met with Yaşar Yakış who was then Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs. Paik is praised as the founder of video art, an iconoclast who spoke through the warped and smashed monitors of his works to dismember the collective unconscious one channel at a time.

"Untitled" (2003) has the head-shaking attitude of a generation coming to after surviving a seemingly terminal passage through the trials of history, where art, while majestic in its unsurpassed genius, served elites and preached to the choir. "Untitled" is humorous, shot through with the television motifs that sent the artist skyrocketing to well-deserved popularity. To that effect and triumphantly, "the Guerrilla Girls" adapted the quintessential orientalist art fantasy "Odalisque with Slave" (1839) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres into "Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met Museum?" (1989), dressing its denuded, neoclassical female figure in a symbol that came to signify the empowered defiance of radical feminism: a gorilla mask. The series of 13 screen prints on paper currently on view were made in the years 1985-1990 in the midst of the Warhol scene in New York's Soho district to tell the story of women in and out of art. And the irony is historic as its core image emerged from a Frenchman's dilated pupils gaping at the mere thought of a Turkish harem, while reading the writings of Mary Wortley Montagu, whose dispatches from Istanbul landed in his lap.