© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

Across the street from Ayvansaray University, the Golden Horn shorefront hospital Balat Or-Ahayim opened as a dispensary built by the local Jewish community in 1885. Named after the Hebrew for "Light of Life," it remains a landmark in the neighborhood as inhabitants and travelers reminisce nostalgic of the late Ottoman era when Jews made up the majority in many districts up and down the Bosporus and its storied inlet where they had lived for the ages that were immemorial to most, only measured by ancient exile for the learned.

Residents historically serviced by Or-Ahayim were Jewish, though they were also workers from the area, making up a generally impoverished class order that continues to fix the welfares of people who live in the environs of the modern hospital as they emerge from the substandard infrastructure that hangs conspicuously from the bottom rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. Walking along the edge of the pavement that cuts off against the waters of the Golden Horn, moored rental yachts and decrepit boats disintegrate into a dazzling array of molded rust and peeled paint, kitschy lighting and ceremonial facades. Ongoing construction efforts to revitalize it as an attractive boardwalk have left the old Jewish hospital as one among a rare handful of historic buildings left for intrepid minds to connect the dots of time as they converge and scatter across the transcendent and intricate cityscapes of Istanbul.

"Op Not Pop" is currently at Plato Sanat, featuring the work of eight artists.

The lights are on at the gate to Ayvansaray University, as its students gather over glaring smartphone chats, smiling upward into the evening beyond that grows all the dimmer once stepping off campus. Friendly security officers turn a switch and the electric turnstiles open automatically into an enlightened space. As is true the world over, universities are the gleaming cores of social fruition, islands of cultural optimism, where the forms of civilization are safely broken down and rearranged to inspire intellectual liberation. Emblazoned in white lettering on a street sign within the walled confines, Plato Sanat gallery is only a few steps from the entrance.

Immediately visible at first look inside the bright, simple gallery space, an inventive channeling of street graffiti is deftly manipulated by Hasan Pehlevan, a man at large under cover of night with a strong tag and a bottle of paint. To add to the group show of eight artists at Plato Sanat, he uncovers the techniques of his ingenious signature design with his 715-centimeter-long mural work "Pattern" (2017) which he threads through his current work like the subtext of a new and provocative aesthetic philosophy. Its visual rendering springs with images of tangled wiring surfacing from illusive holes in the wall, and simultaneously it is a pair of swinging bells.

His manifest ideas are steeped in the prompt to remake the world from the remnants of it that were destroyed in untimely ways. As such, Pehlevan's next work for the Op Not Pop group show at Plato Sanat is "Broken Minaret" (2017). Its concept is based on his experience with found materials in his native Diyarbakir where he recovered fragments of a fresco from an old Armenian church.

Op Not Pop is the clever rebranding of a pair of art movements that while in many ways related are quite distinct. Op Art gained traction in Turkey from its early adherent, the 20th century painter İsmail Altınok, whose works continue to enjoy posthumous appreciation in art galleries in downtown Istanbul. In a few words, Pop Art is salable, and its prestige is won either by its price, or through its effectively speaking to the merging of creativity and advertising in the popular cultures and mass media of capitalist societies. Andy Warhol, who is synonymous with the rise of the movement, famously represented one of the cheapest items at the grocery store, a can of soup, and turned its image into a work of art, by that meaning it became, in effect, priceless. If one of the chief intentions of art is to reflect society and cause even its stubbornest minds to expand despite the deafening and drowning flood of consumer norms, then Warhol achieved that with eye-catching gravity.

"On the Road" (2017) is a meticulously crafted work by Seçkin Pirim, made with 160 pieces of 300 gram Bristol paper cutouts.

Op Art, on the other hand, does something entirely different to the eye. It doesn't merely grab the retina and send messages into its brain to configure values and figures. Op Art conjures the effect of hallucination. It is the art of illusion. For example, in terms of du

alist thought, there could be said to be essentially two kinds of artists. The first one acts like a mirror. They merely depict what is seen objectively, perhaps through an impressionist lens, or a naturalist one. The other works from the inside, recreating the substance or idea of their concern subjectively. Pop Art could be said to fit into the first category, and Op Art in the second. Marcus Graf, the curator of "Op Not Pop" wrote for his exhibition notes, "The artists at the show are interested in formalist ideas as well as in using strategies of Op Art for critically discussing the character of our mediated and manipulated reality." In that way, whereas Pop Art tends widely toward the amplification of capitalist demand, Op Art is an introspective questioning of its aesthetic principles in the interest of mental reformation.

Graf pieced together "Op Not Pop" with a disciplined vision, grouping the variety of works and artists into spatial designations of a certain creative focus. The eight-piece polyptych also integrating a mural "Untitled" (2015-2016) by Eser Tuncer and the oil on canvas "Schloss Balmoral - Colorful" by Ekrem Yalçındağ both employ repetitive, illusive patterns in like-minded fashions, with the work by Yalçındağ conveying more precision overall, leading to the digital prints and two-channel video installation by Ömer Pekin. Inside a darkroom, behind an opaque curtain, a 50-second video by Pekin ventures through the psychological landscapes of the digital era, its sleek paradigms threadbare with ones and zeroes before degrading into basic lines and rectangles of the computerized imagination.

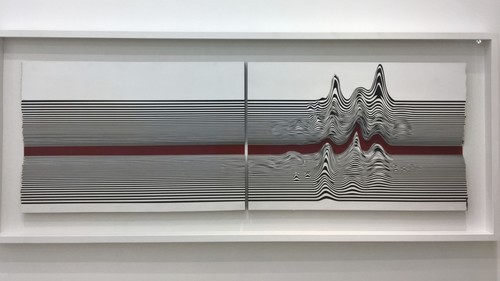

In an effort to craft the effect of technology on the eye, artists like Seçkin Pirim at "Op Not Pop" have taken extreme, painstaking measures. Made with 160 pieces of 300-gram Bristol paper cutouts, her piece "On the Road" (2017) freezes the wavelength into a seismic geology of forms, expanding on the emergence of texture. Graf curated the open-ended rooms at Plato Sanat with a steadfast eye for recurring visual themes. Alongside the work of Pirim are sculptural affinities in the polyurethane creations of Ebru Döşekçi whose piece "Shine" (2017) is a surprising experiment in perspective, as it demands a second glance from viewers who see it head on only to realize that from above a light casts through it to produce shadows in the letters of its title. One of the especially alluring pieces at the exhibition is "Untitled" (2016) another work by Seçkin Pirim, stunning in its sheer intensification of detail. His vision is comparable to the art of Alex Grey, particularly his Cosmic Mirrors series with respect to capturing a spiritualized anatomical peregrination from physical body to soul essence.

Ayvansaray University houses Plato Sanat with a host of contemporary spaces for new ways of thinking to find a voice and an ear within an intellectual respite safe from the cataclysmic buzz of the greater city. Around its corner, such 15th-century edifices as the Jabir Mosque shelters devotees to a man who narrated Hadith, the sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, firsthand, as he was his companion in seventh century Arabia. One is written on the side of mosque: "One day Constantinople will be conquered. How beautiful its conquerors."