© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2024

The youth-vibrant Beirut neighborhoods of the Achrafieh district mix where Armenia Street meets Gouraud, one among untold points of intercultural fusion that mark the peoples of Lebanon with an incomparable, post-literate taste for art. Thoroughly steeped in trilingual society as Arabic, French and English are spoken and written in an impressive balance, historic and recent minorities prompt the need for common expression by more universal, visual means. It is likely a similar mindset that led the Phoenicians to develop the first alphabet, an ancestral heritage that remains a source of local Levantine pride. The contemporary art of Beirut is at the forefront of the latest dialogues that are otherwise choked by language barriers.

"Writing is 50 years behind painting," wrote the avant-gardist Brion Gysin in his correspondence with William Burroughs. It led to the collaborative technique to revise literature into a visual art form, a la the "cut-up" method. Burroughs and Gysin were among many who led the still-unfinished postwar zeitgeist with artistic thought when they merged minds with the Arab-speaking world. Following suit in 1970, the renegade Harvard scientist Timothy Leary was busted in Beirut on his way to meet Jean Genet as a fugitive from a prison break in California.

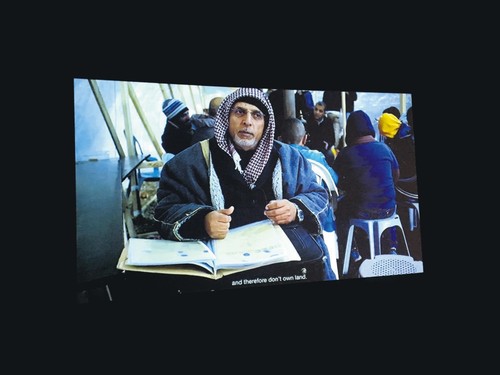

"Ground Truth," by the Forensic Architecture team, on the hardships of Palestinian Bedouin village up against Israeli demolitions.

On Dec. 14, the reputed Epreuve d'Artiste Gallery founder Amal Traboulsi wore a spectacular ensemble for the launch of her book, subtitled, "Chronicle of a Gallery Against a Background of War." For 11 years during the civil war that raged in Lebanon from 1975-1990, destroying much of Achrafieh, and long after its end, the gallery cultivated national treasure troves of creative talent who survived the tragic bloodshed and destructive horror of domestic, armed conflict. A gregariously Francophone line trailed well outside of the former Sursock family residence for her signing, lit by the stunning nighttime facade of Italianate Renaissance Revival architecture with its classical Ottoman features.

The Greek Orthodox aristocrat Nicholas Ibrahim Sursock left his swanky urban estate to the city of Beirut and to its art lovers after his passing in 1952. In common cause, as to inspire post-literate art for a growing polyglot citizenry, the Sursock Museum held its inaugural exhibition remotely, without walls as "The First Imaginary Museum in the World" before opening at the original mansion in 1961. The vision was clear. The crown of institutional support for creativity in Beirut would transcend cultural bounds, and more, it would free itself from historical convention towards a focus on the unprecedented and emergent.

The Sursocks had climbed upward through the fabulous entanglements of Ottoman high society since the early 18th century before building a mansion in 1912 Beirut that now admits the public freely to appreciate contemporary art. As is obvious from his study, which is intact and on permanent view at the museum, his contacts from Egypt to Ireland exposed him to a fine, liberal education befitting an Ottoman dignitary. In the 1930s, he hosted worldly culturati in his lavish Salon Arabe, a columned divan furnished with Damascene crafts, Ottoman-era Turkish silverware and ornately carved wooden reliefs typical to the Orientalist imagination.

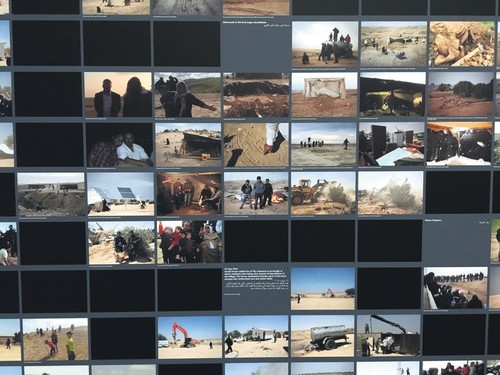

Collected research for the Forensic Architecture team piece documenting the demolition of Palestinian villages.

Beside the Salon Arabe, a small exhibition room is showing "Click, Click: The Repetition of Photo-Graphic Subject Matter in the 19th Century" through Feb. 5, 2018. Gleaned from the Fouad Debbas Collection of 30,000 plus images from Egypt, the Levant and Turkey, the museum has curated a distinct rediscovery of European perspectives on the exotic locales of old Ottoman territory. With contemporary insight, the entrepreneurial 19th century photographs of English, French, American and Italian expeditionaries, evangelists and businessmen are contextualized to reveal pre-modern anachronisms of touristic cliches. While advancing pictorial technology from engraving to film, the early Western photographers to the Orient merely reanimated stereotypes. At the foot of the inconceivable monoliths and the glorious temples of Baalbek, new concepts on point of view, while arguably innovative, were essentially part of a commercialized reproduction process.

Underground at the Sursock Museum, beside the library displaying the archives of the war-resistant Epreuve d'Artiste Gallery, curator Reem Fadda has done certain justice to the Sharjah Biennial for ACT II, the last installation for its 13th year with her exhibition, "Fruit of Sleep" in continuity with the Biennial's off-site project BAHAR curated by Zeynep Öz throughout Istanbul from May to June. In an homage to Haytham El-Wardany, author of "How to Disappear," the spectrum of 24 multimedia works covers a broad intercalated geography of the subconscious. Its essential metaphor points to a vital reawakening, one desperately needed in a region torn by multiple opposing and intractable realisms. Fadda curates disparate elements with the recurring dream logic of a shrewdly humorous Lewis Carroll narrative.

Beirut-based design studies graduate Tamara Barrage opens the darkened entrance with her specially commissioned 2017 series of gelatinous shapes and textures that are as luminous and amorphous as underwater invertebrates. The main space spreads out with "Mujawara / The Tree School" as a Carob tree is strung up hovering in the center of low wooden chairs. Conceived by the Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency (DAAR) co-founders Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, it is a moveable school complete with a translated textbook relocated from its intervention into the Palestinian refugee camps of Bethlehem and transplanted into a nucleus of the Middle Eastern art world. Behind its circular classroom designed under the immemorial arboreal fixture for ecological pedagogies the world over, Berlin-based painter Dina Khouri effects an industrial fashion statement with her abstractionist oils on steel mesh.

Into the smaller of two side halls about the zigzag atrium, the HD video "Somniculus" by filmmaker Ali Cherri metamorphoses his chosen settings from the empty gallery spaces across Paris into a subtle motional composite of faces with eyes shut. Recognized in the last two years by Harvard University and the Rockefeller Foundation, he conjures the archaisms of physical anthropology rendered through the reconfiguration of evolutionary time as an inborn revolution of the sleep cycle. Aside its projections, the virtual designs and

mixed-media paintings of the U.S.-based Palestinian performance artist and game developer Haytham Ennasr excavate the Phoenician and Roman settlements of Beirut with an eye for futurism through an absorbing, interactive VR headset accompanied by an original cartographic collection in the style of a premature Naive artwork made from multiform documentary explorations.

The more overtly social imports of Palestinian representation come to the fore with the ongoing installation "Ground Truth" by the Forensic Architecture team. In detailed paperwork and lucid footage, the struggle to exist for Bedouin villagers in Israel is given meticulously researched voice and substance. The theme is also pronounced in "Electric Resistance" by the Sigil collective, spotlighting a powered clandestine field hospital in a raided Damascus suburb. Finally, the postmodern remnants of the "cut-up" method are resurrected by Korean artist Young-hae Chang and American poet Marc Vogue for "The Art of Sleep." Initially commissioned by the Tate Museum, it is a romp of 20th century cultural references fired in the contemporary technological kiln of somnambulant visions. Its declarations that art is finally and absolutely everything works wonders in contrast to the Sursock Museum environs where the uppish beau monde from the Paris of the East set the stage for the trends of contemporary art to thrive in Beirut.