© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

She held herself with an exquisite poise that spoke volumes of the timeless, creative power of women. The way she sipped her wine-dark tea, how she took soft drags from her constant cigarette, speaking between bouts of laughter with memories of friendship and love, collaboration and invention into her 80th year for exclusive television interviews. She was one of those rare human beings from the greatest generation who lived with dignity and grace through nearly the entire breadth of the riotous 20th century. As they saying goes, they simply do not make them anymore.

For as long as history is written, Füreya Koral will be known as the woman who innovated the age-old Turkish craft of ceramics into a global modern art movement. The latest, posthumous retrospective of nearly 200 of her artworks includes a diverse collection of private and professional documents and photographs. It is a free, public exhibition endearingly titled "Füreya" as she is remembered on a personal, first-name basis. In that way, her legacy is similar to Atatürk's, who she knew as a close friend. Biographic material is fundamental to the curation by Károly Aliotti, Nilüfer Şaşmazer, and Farah Aksoy, which is on display for three months until Jan. 18, 2018. Her life story reads like an individualized, humanist account of the emerging Republic of Turkey.

She came of age in many ways, both personally and artistically, together with modern Turkey's inception and rise. Her earliest memories formed during World War I, as Turks shifted allegiances from the sultans and caliphs of the Ottoman dynasty to a female-liberated, non-expansionist secular democracy. Despite the fact that the imperial "ancient regime" had fallen away, Füreya was a daughter of the Şakir Pasha mansion on the largest of the Prince Islands in the Sea of Marmara from the upper crust of Istanbul. As a young, newly-emancipated and educated Turkish woman, she maintained strong kinship ties with two of her aunts, the renowned engraver Aliye Berger and especially with Fahrelnissa Zeid, whose art also lives on, most recently in a Tate Modern exhibition and a TL 1.26 million ($319,500) sale.

Füreya initially studied French while learning the violin with a Hungarian teacher named Karl who would marry her aunt Aliye. In 1928, with diplomas from two prestigious lycées founded by French and Jewish communities in Istanbul, she aspired to become a doctor and practice in Anatolia, but instead followed a career in French education. Six years later, she received an invitation to Europe from one Mrs. Zeid, her aunt who had newly married the prince of Jordan. They formed a special friendship that blossomed creatively in 1945 when she helped with the opening of Zeid's first exhibition inside the sophisticated Ralli Apartment building in the upscale Teşvikiye district of Istanbul.

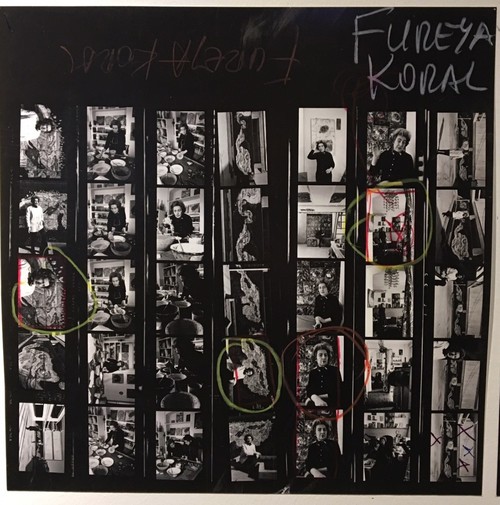

Füreya Koral had a strong artistic and personal bond with famous Ara Güler, who pictured her prolifically in photographs and on film.

While assisting her aunt she contracted tuberculosis. Her condition remained dormant for the next year as she wrote music criticism for the Turkish newspaper Vatan under her married surname, Füreya Kiliç. By 1947, the disease reared, leading her to a sanatorium in Switzerland for treatment. She passed the time there by taking drawing courses with a Polish artist until her favorite aunts sent some intriguing materials for her to try ceramics. During that life-threatening spell of hospitalization, she ultimately discovered her lifelong muse. One photograph from that period is emblematic, showing her blissfully carefree in her hospital bed laughing with a poodle on her lap. The phenomenon of her inspiration runs parallel to the inner evolution of another of the world's most iconic women in art, Frida Kahlo, who was also bedridden when she developed her ingenious creative skill.

Two years following her admission to the sanatorium, she went to Lausanne to attend a ceramic workshop. It was in Paris one year later where she met French ceramicist Georges Serré, who counseled her with his particularly gifted eye for crafting new patterned forms into stoneware pottery. In the City of Light, she met two important art critics, Jacques Lassaigne and Charles Estienne, who encouraged her to open an exhibition. She made haste and wrote Galerie M.A.I. into history when it showed her first solo exhibition in June 1951, as the Maya Gallery in Istanbul did the same only six months later. From the beginning, she was seen as an artist with an unprecedented touch for blending folkloric and modernist styles. By the time her work appeared in a group exhibition in 1973 she was known in six countries outside of Turkey.

The retrospective, "Füreya" fills the Akaretler building site from top to bottom throughout its coursing labyrinth of rooms and halls within the 19th century architectural complex known as the Sıraevler, from the Turkish for the "row houses" that served as the residences of prime dignitaries in the employ of the Ottoman Empire at Dolmabahçe Palace. It's a multiparty effort with a range of noteworthy partner organizations like SALT Research, the Ara Güler Archive and Research Center and Lycée Francais Notre Dame de Sion, where Füreya studied French in the newborn Turkey of the 1920s. The various contiguous, multimedia exhibitions coalesce in points of unison and emphasis with an impressive, narrative scope linking the artist herself and her works with the greater local and global contexts highlighting the significance of her artistic contributions to human creativity from the dawn of time to the contemporary.

Immediately straight through the entrance into the heart of the exhibition, a collection of works hang on the wall from her initial wave of color sketch painting to display her immediate capacity to balance the seriousness of her devotion to craft with the effective lightness that all great art captures for its often meandering appreciators. And yet, her development was then clearly unripe, lacking the depth and voice that she would become known for passing through fired clay. Scarcely dated, pieces from her black-and-white series from 1951 surfaced from her Turkish subconscious with images of high-domed mosques and Ottoman cemeteries. At the time, Füreya traveled often between Istanbul and Paris struggling with physical ailments, and even checked her ceramic kiln as a baking oven so as not to prompt questions at the border.

One shaped and blazed handful of soil at a time, she went on to sweep her nation before the world with the transformative spirit of modern art. From the traditional collectivism visible in the Hittite pottery of prehistoric Anatolia and the vibrant turquoise glazes in Islamic architecture, she carved and sculpted modernist, individual expressionism out of time to sharpen the contemporary aesthetic focus. "Füreya" is a triumphant retrospective as it takes the public on a venture through the mind of a woman who painted with the textures of earth and visioned with the heat of the sun. After evolving from her lithographic frames, she became the peerless artist of her renown, mastering such self-styled techniques as reliefs on plates, radiantly paneled murals, which are still exhibited in public spaces, and model houses, among virtually infinite metamorphoses of ideas that she put into practice enough to shape time itself.

In 1991, American scholar of shamanism Terrence McKenna coined the phrase "Archaic Revival" to reconsider the modernist future as a function of prehistory. It is arguably in a kindred direction that Füreya pursued her life's work while resurrecting ancient Anatolian and Mexican motifs. As one among the first generations of modern Turkish women, she brought the defining traditional craft of her country out from the obscurity of mosques and museums to the contemporary light of patisseries and hotels. One of her very first ceramic pieces titled "Fille de la Nuit" is based on the form of the book and reimagines modernism as a cyclical return to creative evolution without precedent.