© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

In its heyday under Sultan Abdülmecid I, while international naval conflicts raged around the Crimean Peninsula, the musty, searing air of the Tophane cannon foundry was filled with tubercular bacteria, as were its floors where blistery-eyed men heaved and wheezed over the casting grind to round spheres of iron into weapons of war. From pits caved into the bare earth, laborers fumed amid the ceaseless, fatal sizzling that pierced through the acoustics of the high-walled domes as they slid molten metals with painstaking nerve beside flame-retardant barrels of honey and cisterns of water emptying with a blast over the factory floor when a fire blazed.

On Oct. 31, in the Tophane Sarnıç (Cistern), 29 untitled canvases by the late, contemporary painter Ismail Altınok appeared on the walls of the medieval weapons plant for the current gallery show until Nov. 26, organized by his son, Dr. Mehmet Altınok. He is a proponent of Op-Art, a modernist tradition that designs complex and repetitive geometric forms to create manual, two-dimensional optical illusions. Its effect is an analog treatment of the bygone abstractions of metal and fire, honey and water, blood and sweat as they mixed and coursed through the historic space. The freethinking British biologist Rupert Sheldrake refers to such metaphysical influences on the patterns of time as morphic resonance.

The Tophane-i Amire Art and Culture Center's Sarnıçlar Gallery is currently showing 29 untitled paintings by Op-Art modernist Altınok.

Born in the southwestern Turkish province of Burdur in 1920, Altınok soon passed the local Taurus mountain range to seek an education in Ankara, where he launched his creative vocation as an artist with an unrivaled grip on the global trends of the day. After completing his studies in 1943, he held his first painting exhibition in Ankara in 1948. Seven years later he went to Paris for a month to participate in a group exhibition. By 1959, the Italian government supported him financially as he painted freely in Rome for another four months. Along with his fellow Ankara schoolmates, such as renowned painters Eşref Üren and Cemal Bingöl, he represents the generation immediately preceding contemporary Turkish artists at work today who exist on the battered front of the nation's cultural horizon with rare and obscure openings such as at the Tophane Sarnıcı, to reimagine the domestic field often plagued with deafening nostalgia and intractable rhetoric. Following in the dizzying footsteps of Altınok, new artists in Turkey advance traditional forms readily inspired by the present with freshly vital, and forwardly positive means of self-transformative expression.

The year Altınok went to Paris, the Galerie Denise Rene held its defining Le Mouvement exhibition during April, essentially establishing Op-Art as a recognized contemporary form along with its aesthetic pair, kinetic sculpture. The latter sought to permeate exhibition space, while the former suffused the senses of its viewers from within. Both were absorbed in the idea of motion as a pivotal fixation for pieces that were often drawn from excavations of film technology and avant-garde experimentalism. The show launched careers, as for Jesus Rafael Soto, who would integrate Op-Art into Venezuelan visual culture. It also lionized iconoclastic celebrities like Marcel Duchamp, curating his art of industrial decontextualization from the interwar period comparatively with younger artists whose work was based on the scientific introspections of the postwar tech boom.

From 1945 to 1960, the Paris School had its way with many Turkish artists, among them were Abidin Elderoğlu, Hasan Kavruk and Ismail Altınok, who developed formal abstraction into his special approach to Op-Art. To lyricize the recognition of shapes was the modus operandi for the initial artists who found muses in the Paris School. Within its growing movement of adherents, Altınok sought to visualize a pictorial language through positive-negative color arrangements, which he achieved with mathematical precision. At the same time he juxtaposed illustrations of natural rhythms into geometric repetitions, skillfully rendering optical illusions in paint. His works transfix viewers to experience art viscerally, drawn into mutual interactions between the globular eye and the rectangular frame as directed by the manifestations of one visionary mind. When Altınok won the The State Painting and Sculpture Exhibition Achievement Award in 1975, it was clear that Op-Art had a place in Turkish art history.

Altınok, trained in the Paris School since the 1940s, had a stunning capacity to paint optical illusions.

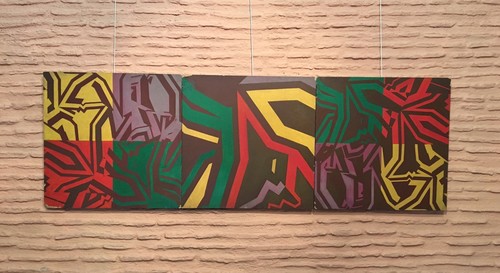

Although his earliest works were essentially landscapes born of the Anatolian countryside with its infinite knolls stretching out over the vast glacial plateau, the current Tophane exhibition revolves around his evolutionary concentration on Op-Art. Walking through the industrial green doors into the cistern, with the minarets of Nusretiye Mosque looming overhead, the immediate canvas in sight is a triptych in four colors, etched and shaded into a sharp, metallic web of diagonals and points. The piece depicts the fundamental shift in his aesthetic transition from the purely abstract to the optical illusion.

Housed in three contiguous rooms against flat brick aside mahogany-hued doors, the Op-Art of Altınok, as currently exhibited in Tophane, could be said to have emerged over the course of three basic developments. Firstly, a pair of his paintings in the collection are visibly more nebulous than the rest, almost completely vague but for pasty smears and runs of the various brush sizes he employed, dashing this way and that with a relatively colorless palette in one, and a more contrasted saturation in the other. They have all of the signs of a nascent chaotic phase before coming to fruition with more exacting clarity. Secondly, there are certain pieces that demonstrate a less diverse, more rudimentary and defined relationship to color, yet that play with the perception of texture through the placement of isolated, multilayered shapes. In the second phase, he is painting multiple canvases in one. From there, he departs from the motifs in the triptych toward repetitive patterns within concave-convex angles, provoking a sense of warped perspective and virtual space created by the mind when looking at such disorienting and unfamiliar variations in form and color. Finally, most of the paintings displayed at his Op-Art exhibit are dedicated to one central theme at a time, which he exhausts and intensifies with minute color grading and the subtle expansion and contraction of mirrored forms.

Ultimately, the Op-Art movement was generally a critical failure. Those who initially perused its systematic intricacies were left unsatisfied with the medium of paint as a probable vessel to develop the perceptual revolutions triggered by computer science. It had its grandest hurrah at MoMA in 1965 with "The Responsive Eye" exhibition, although its origins stem from the 19th century treatise, "Theory of Colors" by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The most famous work of the Op-Art movement is "Blaze" (1964) by Bridget Riley, whose style followed her experience in advertising, as it did for her earliest contemporary, Victor Vasarely.

Into his eldest years before he passed away in 2002 at 82 years of age, he would sit with an accomplice under the shade of a tree and look out over a verdant field to blissfully reflect the soul of the land one brushstroke at a time. He gave the earth he painted new life with his highly visible, post-realist daubs of formless color that ran across his canvases like deep runnels springing with spiritual vivacity. The pieces at his current, posthumous Op-Art exhibition run parallel as they infiltrate the left brain intellect with a powerful invitation to join him in the afterlife of his crafty intuition, his infinite visions. Crystalline, rainbow triangles and flat, labyrinthine spirals move like surprise hallucinations and unforgettable mirages as they rise up from the unseen source of human creativity and vanish in the instant blink of a broken stare.