© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2025

Among the Islamic arts, calligraphy has distinctly risen to universal appreciation for its pure aesthetic appeal. As a glorification of visual language into a stylistic and functional art tradition, Islamic calligraphy derives from the religious tenet that forbids the illustration of the sacred. It is a belief shared among Semitic linguistic cultures whose liturgies are in Arabic and Hebrew, traditionally meaning that of Muslims and Jews.

A closer and deeper look at the art of Islamic calligraphy reveals that it is not an expression of spiritual prohibition, but more truly, a medium for creative fulfillment through the hallowed beauty of language itself. It is the discipline of solitude in the stylistic craft of imprinting one single letter at a time, word by word by verse by page, manuscript, and canvas. And as is common to both Hebrew and Arabic, its alphabets are practically devoid of vowel lettering, further emphasizing the holy nature of writing as a way to visualize and guide the ineffable and formless breath, as a metaphor for the unseen spiritual realm through earthly shapes and sounds to the concept of total unity, of completion within and without human artistry.

DemArt is a boutique gallery of Islamic calligraphy in the heart of a neighborhood that continues to honor its past as a Bosporus shorefront community that nourished a linguistic diversity to rival Jerusalem. Its lost Armenian, Greek and Jewish communities fought as kids and intermarried as adults all while observing every holiday under the moon and sun together. They are remembered as a historic example of intercultural tolerance. Kuzguncuk nostalgia has become a model for social scientists attempting to resew its past community fabric as present-day cities across the globe struggle with unprecedented and multifaceted population influx.

The opening of DemArt along a quiet, garden alleyway in a historic home signals a new era in the meaning of social tolerance through art, as the dominant religious culture of the past has resettled within the secular modernism of the prevailing Turkish culture. Its location is certainly not central to the main avenue of the neighborhood where the many local art galleries curate the latest trends in expressionism and caricature. Inside its three stories, the halls are most often absent but for a single host, Ruhi Koca, whose smiling welcome facilitates patient appreciation of the meticulously detailed, gorgeously crafted and surprisingly original pieces of Islamic calligraphy on display.

Its exhibitions are curated with young ateliers from across Turkey, and with special calligraphic commissions from the Iran-based atelier, Ganjineh, after which they are illuminated and framed by Muhammet Mağ at his Üsküdar workshop. Mağ received his İcazet, the traditional merit of authority to sign original works and to teach, from the renowned master calligrapher Hasan Çelebi, who still lives in Üsküdar. In 2013, he graduated as a student of the talik technique under Çelebi, who personally invited Mağ to Istanbul after hearing that he opened and ran the very first, although short-lived calligraphy atelier in his native Erzurum.

Based in Üsküdar for the last nine years, he is not far from DemArt along the Bosporus esplanade of Paşa Limanı Avenue closer to the ferry pier and central market where some five centuries ago Mihrimah Sultan sponsored the architect Mimar Sinan to beautify the cityscape with the timeless architectural gifts of his unmoved domes and spires. A year and a half ago, Mağ opened DemArt with Ruhi Koca to blend the contemporary curation of Islamic calligraphy with the multicultural heritage of Kuzguncuk. Any calligrapher who has obtained the İcazet is eligible to exhibit at DemArt, which typically requires eight years of commitment to the master craftsmen ustas who have preserved time-honored techniques over generations of personal transmission.

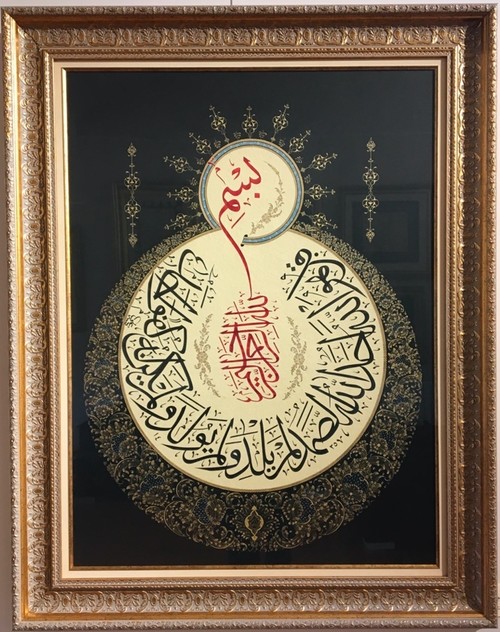

The works on display at DemArt are as diverse as the artists themselves. Said Abuzerow hails from Russia, demonstrating his talent within violet and gold illuminations of Quranic verse, signing the names of the first four caliphs inside floral seals of eight-pointed, Ottoman stars. Meryem Nourizi is from

Iran, and now lives in the Old City of Istanbul in the district of Fatih. Her matte jade embellishments and rectangular-framed passages are lucid, visual realizations of the elevated syntactic alignment in Islamic scripture.

Other artists from the Mağ calligraphy atelier in Üsküdar exhibited at DemArt are Ali Zaman, originally from Kirkuk, Iraq, whose individual sense of novelty shines through an often rigidly perceived discipline of traditional forms. In one of his pieces, he plays with the motif of discontinued circles, as the contents of one pours into the next, forming linguistic crescents in a sequence of abstraction and color through elegant Arabic lines. And Halil Mantik explores the frame of the manuscript page and its illumined sacred text with a novel freshness, evoking the Asemic and Post-Literate language arts and visual poetries of his secular contemporaries.

"The old masters worked to preserve a dying tradition. Now, calligraphy is here. It's alive. Ten years ago, this calligraphy was not shown in contemporary galleries. Calligraphers are now experimenting to make it new.

It's international. It's beautiful for everyone," said Muhammet Mağ at İncirhane, a cafe close to his atelier, where he sat to converse under an artwork blending Chinese and Islamic calligraphies with a fellow student of the great Hasan Çelebi, a man from South Africa named Muhammed Hobe. "Calligraphy is a geometric art. It is mathematical. Letters must be drawn to proportion, like in any art. And as an art form it is originally part of Turkish civilization, not Persian or Arabic. To become a calligrapher is not just about art or talent. It builds character. It's about becoming a human being."

Soon after the turn of the millennium, Muhammet Mağ arrived to Istanbul with a reputable academic career and a successful one-man show behind him, albeit from his confessedly artless hometown of Erzurum where he had to close its maiden calligraphy atelier that he himself founded due to lack of means and interest. He had only a single pair of pants, two shirts and five Turkish liras, and no one in his family back home even understood art. He would go on to illuminate the works of Hasan Çelebi, one of the world's most sought-after calligraphers, for the next six years in his Üsküdar workshop before becoming a master calligrapher with a distinct artistic signature. As an illuminator working in color, he often fades crimson hues into the conventional black ink of tradition.

Muhammet Mağ is a singular curator, whose Islamic calligraphy atelier is unexpectedly contemporary behind its nondescript door in a dusty Üsküdar office building. He jokes that it takes 34 hours a day to become a calligrapher. He identifies originality in the highly disciplined, traditionally religious art in new pieces that are able to manifest the spirit of individuality objectively and universally for every pair of eyes that would grace its surface. DemArt is currently preparing its gallery for a special exhibition scheduled to begin in November titled Esma-ul Husna dedicated to the names of God. While there are 99 names for God in Islam, the calligraphers will surely reinvent them with infinite creative splendor.